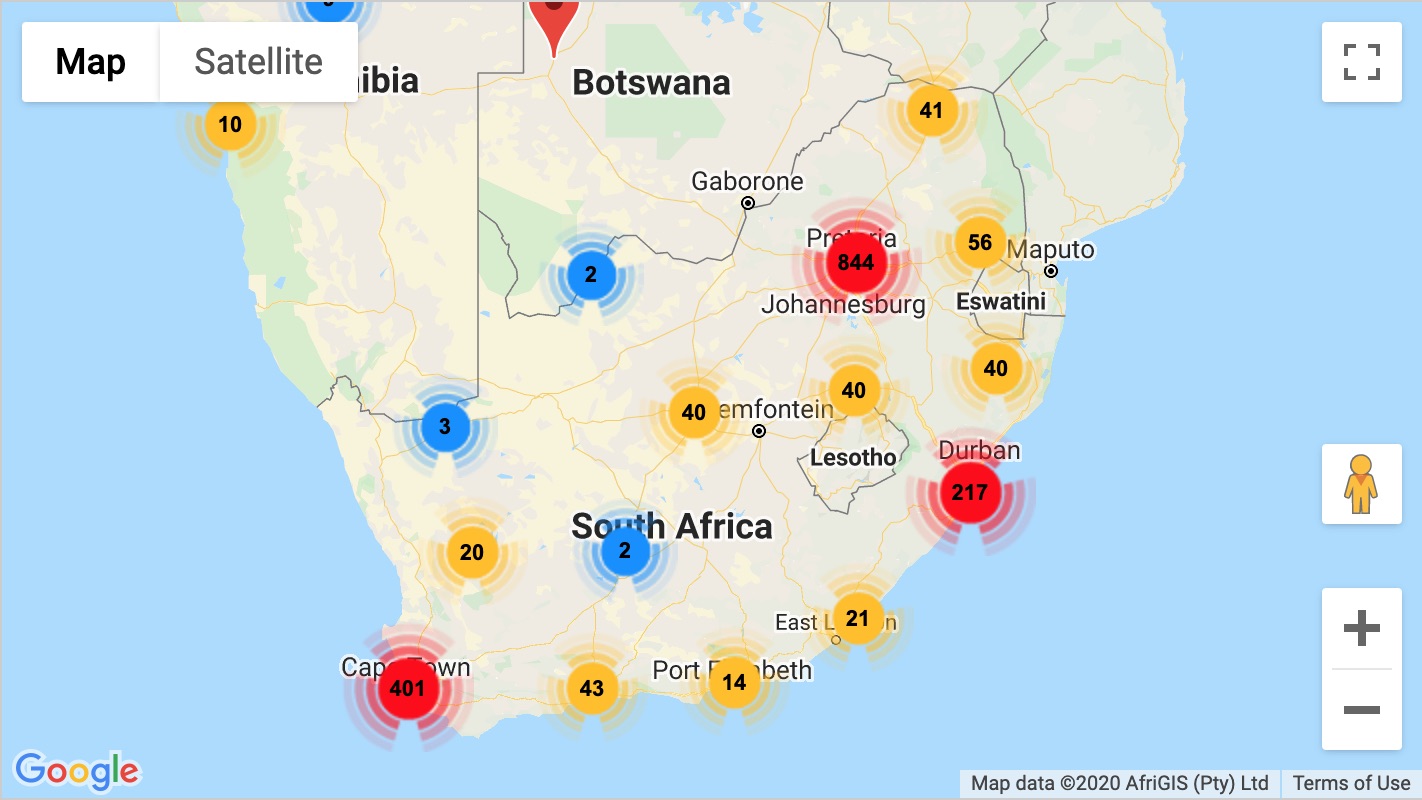

Snakebite in southern Africa

Snakebites can be serious and sometimes life-threatening and require swift and appropriate treatment. The majority of victims do however, experience a full recovery without the administration of antivenom.

In many instances venomous snakes will bite in self-defence and inject no venom at all – such bites are referred to as dry bites. Another possibility is that a potentially deadly snake may inject a small amount of venom – far too little to do serious damage – and, in such instances, antivenom would not be required.

Doctors need to do a thorough assessment of the condition of a snakebite victim before antivenom is administered.