Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

We have almost four hundred thousand members on our various Facebook and social media groups and pages, and the most frequently asked question is, “How do you identify snakes?”

Some people seem to think that identifying snakes is a supernatural skill that only experts have, but it is not that difficult to learn. There are a few very important factors that go into identifying a snake:

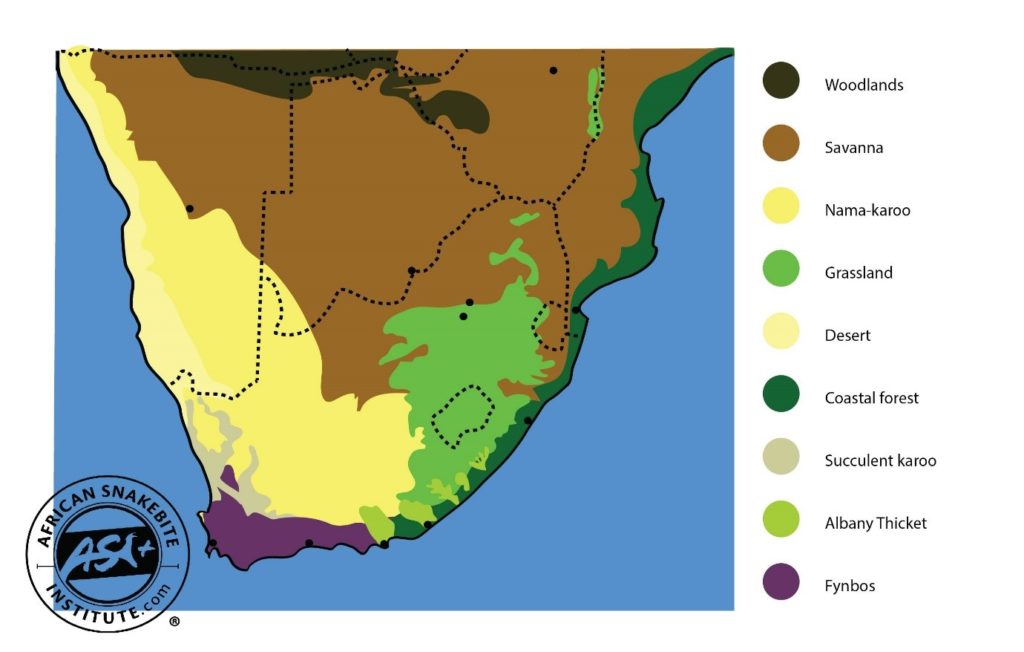

Distribution

One of the first factors any expert will consider when asked to ID a snake is the location. Where was the snake seen? Distribution is very important when it comes to identifying snakes. Many species only occur in certain areas, and so once you know the location you can rule out several other species which might confuse the issue. A large black snake in the Western Cape cannot be a Black Mamba and is more likely to be a Mole Snake or Black Spitting Cobra, as Black Mambas only occur on the warmer eastern half of the country. It could also be a very dark Cape Cobra.

You will notice on our ASI Website, the ASI Snake Profiles, ASI Snakes App, as well as in all good field guides, that there is a map of southern Africa indicating the distribution of the species.

There is always the chance that it may be a hitchhiker – a snake accidentally transported with produce or equipment – or a snake that has escaped from a private collection or snake park, but this is uncommon. When considering distribution, the most likely option is usually the correct one. A small grey snake in your house in Johannesburg is more likely to be a Herald Snake than a Black Mamba, as Black Mambas are only known from well north of Pretoria in Gauteng province.

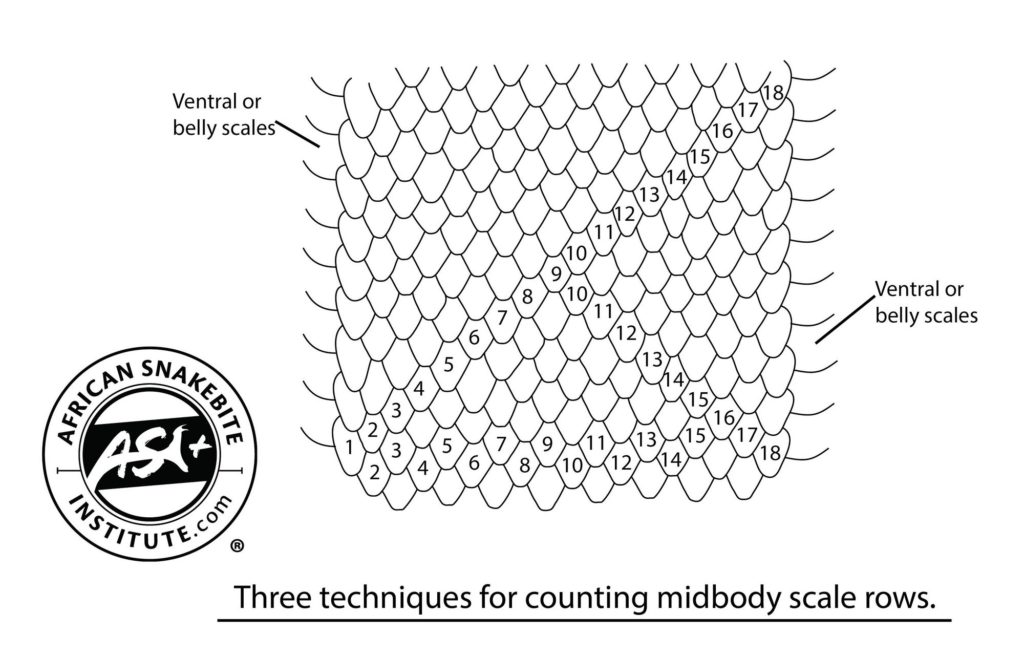

Scales

Scales also play an important role in identification. Are they keeled or smooth? This question can rule out a lot of options and help clarify the identity. If a clear view of the snake is obtainable – either in person (without jeopardising your safety) or by means of a photograph – scale counts can be done. Head scales are important and are often unique for a species. Most digital cameras can zoom well and clear photographs of the side of the head can be captured. This will allow one to look at the upper labial scales, the pre- and post-ocular scales as well as the temporal scales. In many groups, such as the green and bush snakes of the genus Philothamnus, the number of temporal scales and the number of upper labials making contact with the eye are key in telling them apart. Scale counts are also very useful for small black snakes such as stiletto snakes, purple-glossed snakes, Wolf Snakes and Natal Black Snakes.

Colour

Both the colour and markings on some snake species vary dramatically throughout their range. Once you have an idea of what these colours could be, it makes identification easier. Some species always have a certain colour trait – such as a light upper lip – which can differentiate them from other similar looking species.

Length

The length of a snake is difficult to gauge, and we find that around 80% of people cannot estimate it correctly. Getting a general indication of length does help with some identifications. People more accurately indicate a snake’s thickness than length, and asking them to compare the snake’s girth to a broomstick or thumb is helpful. Be aware of forced perspective in photographs – an instance where the snake is held close to the camera on a stick, causing it to look a lot larger than it really is. One can often estimate the size of a snake by considering its proportion to surrounding objects in the photograph such as bricks (around 20 cm long), floor tiles, and grass. Take into account that the average distance between the width of a vehicle’s tyres (if measured from the outside of the tires) on a dirt road is 1.8 m.

Have a good look at the morphological features of a snake. Does it have a long, thin tapering tail or a short, bulky tail? Is the head distinct from the body? Is the head elongate or is it short and rounded? Is the body round and muscular or more flattened?

Behaviour

Knowing a bit about a snake’s behaviour also comes in handy when identifying it. For instance, Common Slug-eaters tend to curl up in tight balls when threatened, and Rhombic Egg-eaters coil and uncoil – rubbing their keeled scales together to create a hissing sound. Herald Snakes often flatten their heads to expose their brightly coloured lips when in a defensive posture, and cobras form impressive hoods when cornered in an attempt to deter their attacker. There are exceptions to the rules of behaviour, and we occasionally see Mole Snakes lifting their heads off the ground and even flattening their necks, making them easily mistaken for a cobra. Such behaviour can be learned by observing wild snakes, reading up on the ASI Snake Profiles, or studying the Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa by Johan Marais.

The easiest way to educate yourself is to start off by learning about the snakes in your area. We have a wide variety of free resources available on our website, as well as our incredibly popular free app, ASI Snakes. One of the fun features of the app is the quizzes one can take, that test your knowledge of snakes at different levels of difficulty. Give it a try!

Our Facebook page Snakes of Southern Africa is also a great way to test one’s ID skills, as multiple snake images are uploaded daily from all regions of southern Africa, giving one exposure to a variety of species and colour variations to try and identify. You are also encouraged to ask the more knowledgeable experts on the page how they identified a certain species, and to point out important features to you.

We have just launched our brand-new online course – Advanced Snake Identification. This eight-part course covers groups of snakes that are tricky to identify as well as frequently encountered snakes, and medically important snakes. It has self-tests throughout the course and a final exam. The pass rate is 80%, and successful candidates will receive a digital certificate in Advanced Snake identification from the African Snakebite Institute.

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

Rangers Book Combo 1

Rangers Book Combo 1

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00

ASI Book Combo 1

ASI Book Combo 1

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Sign up to have our free monthly newsletter delivered to your inbox:

Before you download this resource, please enter your details:

Before you download this resource, would you like to join our email newsletter list?