Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Effective antivenoms were first developed in 1886 and, in South Africa the first antivenoms were produced in 1901.

Different snakes were used locally for antivenoms and this changed over the years. Initially just Puff Adders and Cape Cobras were used as these accounted for the majority of reported bites. In 1938, Gaboon Adders were added to the mix. During the second World War, the demand for antivenom increased due to the number of soldiers in remote areas. Rinkhals was added to the antivenom production during this time. By the 1970s, three mambas were added (Black, Green and Jameson’s) as well as Snouted (Egyptian) Cobra, Forest Cobra and Mozambique Spitting Cobra.

Initially the antivenom was produced by the South African Institute for Medical Research (SAIMR) but in recent years it was renamed to the South African Vaccine Producers (SAVP) which is part of our National Health Laboratories.

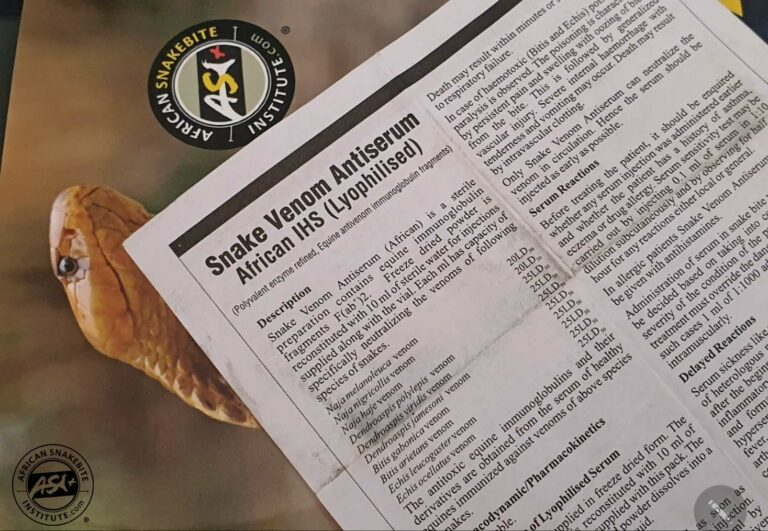

The current polyvalent antivenom, in which the venom of 10 species is used, has been manufactured since the late 70’s. The 10 species included in the mix are: Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis), Green Mamba (Dendroaspis angusticeps), Jameson’s Mamba (Dendroaspis jamesoni) Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus) Puff Adder (Bitis arietans), Gaboon Adder (Bitis gabonica) Forest Cobra (Naja subfulva – previously N. melanoleuca), Snouted Cobra (Naja annulifera), Cape Cobra (Naja nivea) and Mozambique Spitting Cobra (Naja mossambica).

While the polyvalent antivenom may produce cross coverage for the Black Spitting Cobra (Naja nigricincta woodi), the Black-Necked Spitting Cobra (Naja nigricollis) and the Zebra Cobra (Naja nigricincta nigricincta), little research has been done to show how effective it is for these species.

Of the 10 species in the mix, it appears that the SAVP polyvalent antivenom is least effective for Mozambique Spitting Cobra bites and large amounts of antivenom injected within 2-3 hours is recommended, whereafter the antivenom appears to be largely ineffective and victims often suffer severe morbidity. Having said that, the administration of polyvalent antivenom for Mozambique Spitting Cobra bites is still recommended as it will break down toxins in the system and may well prevent other organ damage.

SAVP also produce a monovalent antivenom for the Boomslang (Dispholidus typus) which is highly effective in treating bites. Echis monovalent antivenom is made for the Saw-scaled Vipers further north in Africa.

The immunisation process to make antivenom has been well defined and regulated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and strict protocols must be adhered to. In South Africa we use horses, because they produce a good immune response, are easily managed and after 9 months of immunization up to 9 litres of blood can be drawn ever second month. The serum is removed from the blood and the excess blood is returned to the horse thereafter. In recent years we have experienced a severe shortage of antivenom in southern Africa. Various reasons including power outages have been blamed for this shortage. Note that it is a shortage of antivenom and not of snake venom. There is more than enough snake venom available for the immunisation process. This has resulted in a variety of foreign antivenoms being imported and are sold under section 21 of the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. It is quite a vigorous process where several documents need to be completed and submitted for each and every treatment.

Unfortunately, several of these imported antivenoms do not cover the venom of all of our highly venomous snakes and most of them have not been subjected to clinical trials. One therefor must rely on the manufacturer’s recommendations on dosages and such recommendations are often untested and inaccurate. For some of these imported antivenoms you may require as many as 60-80 vials for a serious Black Mamba bite. As no hospitals stock such quantities these antivenoms are largely ineffective.

The WHO declared snakebite a neglected tropical disease in 2017 and are attempting to reduce snakebite fatalities and morbidity by 50% before 2030. This they hope to achieve through education and awareness to reduce snakebite incidents and developing new antivenoms and more effective treatment. There are various institutions researching antivenom, including synthetic antivenoms, and millions of dollars have been put into this research. While there are promising results, no new antivenom has been developed to the stage of being commercially available. While some drugs like neostigmine can be used in the short term in some neurotoxic bites to manage symptoms, other drugs like vitamin C and vitamin K as well as cortisone and antihistamine have very little effect on the severity of a serious snakebites and are not lifesaving.

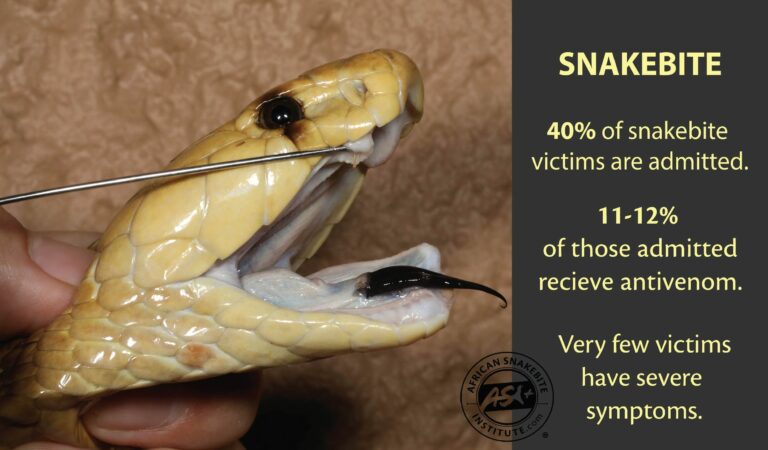

One of the imported antivenoms – Panaf Premium has WHO approval and initial results on both humans and pets are encouraging. It is a lyophilised product (reduced to a powder) that does not require refrigeration and has a 4-year shelf life. The price per vial is just over R2000.00 but the downside is that you need double the number of vials as opposed to SAVP polyvalent antivenom. Therefore, roughly double the cost per treatment. One of the biggest problems with SAVP polyvalent antivenom is that around 4 out of 10 patients have anaphylaxis due to an allergic reaction to the horse plasma. And this requires urgent medical intervention. For this reason, antivenom is only administered in a hospital environment by trained medical professionals. To date none of the patients treated with Panaf Premium in South Africa have had anaphylaxis. Roughly 9 out of 10 snakebite victims that are hospitalised do not receive antivenom, purely because the level of envenomation does not justify its administration.

In pets about half of the dogs that end up at a vet after a snakebite do not require antivenom. While the identity of the snake responsible for a bite may assist the doctors or vets in that they will have a better idea of what symptoms to anticipate, the identity of the snake responsible for most bites is unknown. Both doctors and vets do not treat snakebite, but the symptoms of a snakebite. If the symptoms are severe enough, be it a neurotoxic bite with progressive weakness, a cytotoxic bite with progressive swelling, or a haemotoxic bite where the blood clotting mechanism is compromised, antivenom may well be administered.

For humans the initial recommended dosage of SAVP polyvalent antivenom in a severe puff adder bite is 5-6 vials, whereas in cobra and mamba bites the patients should receive at least 12 vials. For dogs most vets will start with 1 or 2 vials of SAVP polyvalent antivenom. In humans the antivenom would be infused via a saline drip over half an hour. And if the patient does not show marked improvement, further antivenom may be required. This is usually done by analysing the results of regular blood tests.

In severe snakebite, the early administration of antivenom and in the correct dosage, may be life saving and could reduce tissue damage significantly. When required the sooner the antivenom is administered, the better.

The only treatment for severe snakebite envenomation is antivenom. There is no other known substance for both humans and pets that is effective. Unfortunately, there are several myths and folk stories that may be resorted to, and this includes vitamin K injections, vitamin C injections, various ointments and natural substances, and untested “antivenoms” made in various ways, including extracting blood from snakes. In the case of pets and farm animals people resort to forcing charcoal or milk down animals throats, cutting the tip of the ear to “bleed out the venom” and even injecting petrol. The latter is barbaric, extremely painful and does absolutely nothing to neutralise the venom. The correct treatment for any serious snakebite in humans is hospitalisation as soon as possible where the patient will be stabilised, treated for pain, and intubated and ventilated if breathing is compromised. In the case of pets and farm animals, consult a vet immediately. There is no first aid for pets or farm animals bitten by a highly venomous snake.

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Sign up to have our free monthly newsletter delivered to your inbox:

Before you download this resource, please enter your details:

Before you download this resource, would you like to join our email newsletter list?