PLEASE NOTE. Our offices will be closed from the 12th of December 2025 – until the 5th of January 2026. Last date for orders will be the 8th of December 2025. Any orders placed after the 8th of December 2025, will only be dispatched after the 5th of January 2026.

You’re watering the garden and discover a shed snake skin in a rockery. Where is the snake? What is the snake? How big is it?

When snakes grow, they get too large for their skins and need to slough the old skin. The process of shedding the old skin is known as ecdysis. In humans, and most mammals, we shed our skin in tiny pieces all the time. In snakes and many other reptiles, the shedding of old skin is one process and is often done in one whole piece. In snakes, shedding may occur between four and twelve times a year, depending on the growth of the snake and the humidity of the area it resides in. Snakes also shed when a wound has healed after an injury.

Prior to shedding snakes will become a dull colour, and the eyes turn a milky-blue colour as chemicals separate the old eye cap from the newly formed one. We term this state as the snake being “in the blue”. Snakes usually hide at this stage as their vision is impaired and they are vulnerable to predators.

Snakes may have increased blood pressure at this stage, causing the body to swell and stretch the old skin. The whole process may take a few days to a week or two and the snakes usually stop feeding during this period.

The snake will then find a rough surface, such as a log or rock, and rub the nose until the old skin starts coming loose. The snake then slides out of the skin, causing the skin to turn inside out. The whole skin comes off, from the tip of the nose, the eye caps, to the tip of the tail – including the eye caps. These skins will stretch up to forty percent, and the snake skins which are found are larger than the actual snake and are not a good indication of the size of the snake.

Once snakes shed the old skin, they know many predators will pick up the scent of the shed skin and the snake is at risk. Generally, snakes move off after shedding. Some snakes like Black Mambas and Boomslang may be resident, if undisturbed, and may have an area or single tree or bush that they shed the skin in, and you may find more than one skin at this area.

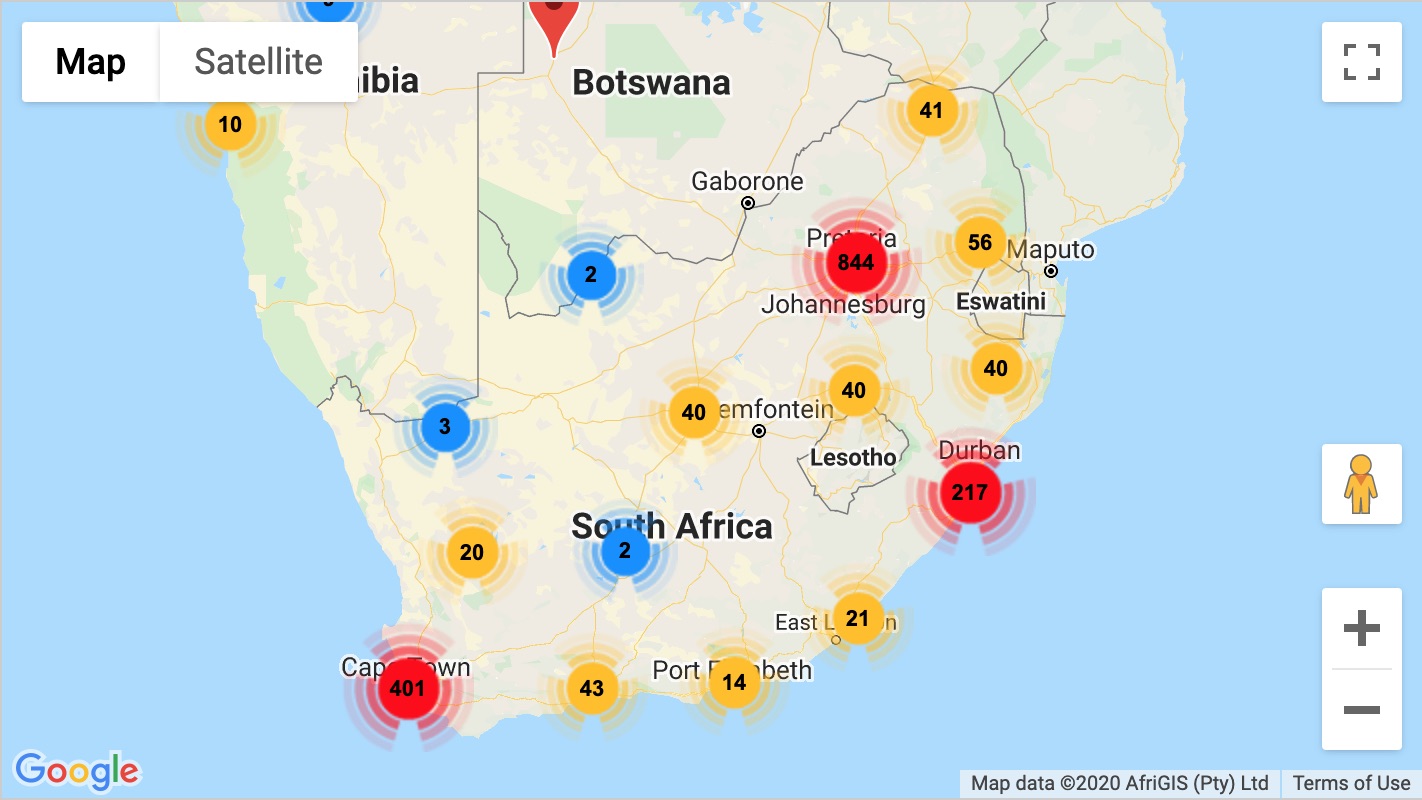

Identification of these skins is tricky and we generally need to start counting scales to confirm the species. Snake species have a unique scale count, although a number of them may overlap with other species. In many instances, the distribution will help eliminate species that don’t occur in the area and allow us to narrow down the potential species the skin belongs too. Other features such as keeled scales will exclude many other species. Some skins such as Rhombic Egg-eaters, Southern African Pythons, Puff Adders or Spotted Bush Snakes will retain the pattern in the shed and can be easy to ID.

It is useful to keep in mind that snakes have large belly scales, and small pieces of skin found in the garden without large belly scales are probably those of garden skinks.

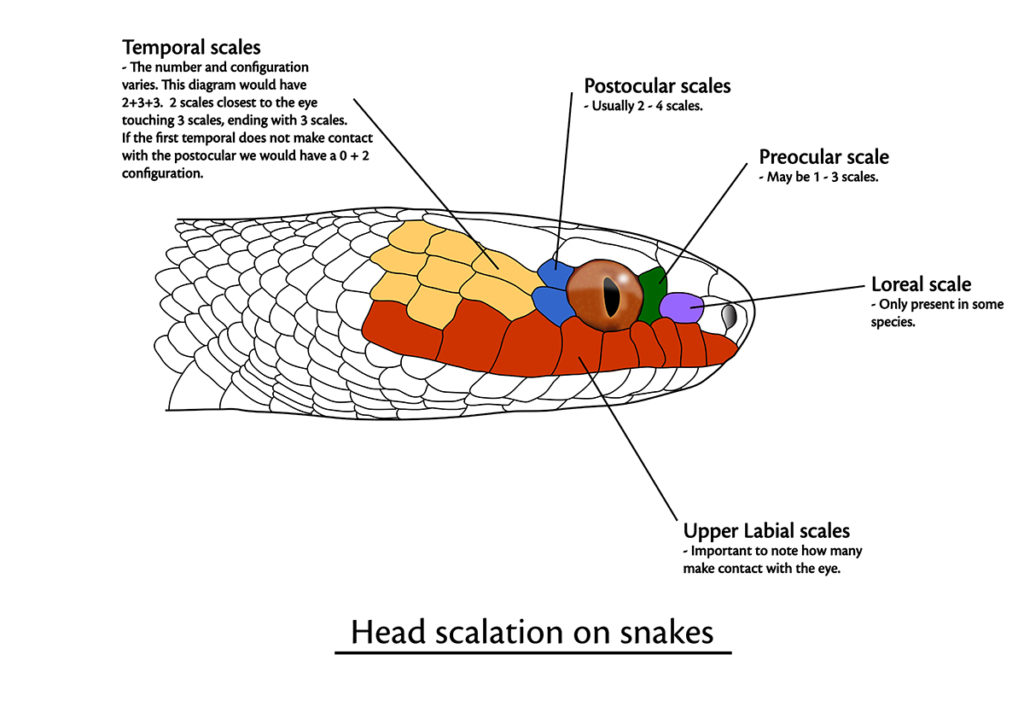

As for the rest of the skins, there are three areas we need to focus on to count scales:

The first section is the head. The upper labial scales that make up the upper lip can be counted, paying attention to how many are in contact with the eye cap. For example, in Angola Green Snakes, three upper labial scales make contact with the eye. In the Green Water Snakes only two upper labials making contact with the eye.

The temporal scales behind the eye are also very important and are usually unique to a group. Cape Cobras have a number of large temporal scales whereas Mole Snakes have a series of small scales that are similar to the scales on the neck.

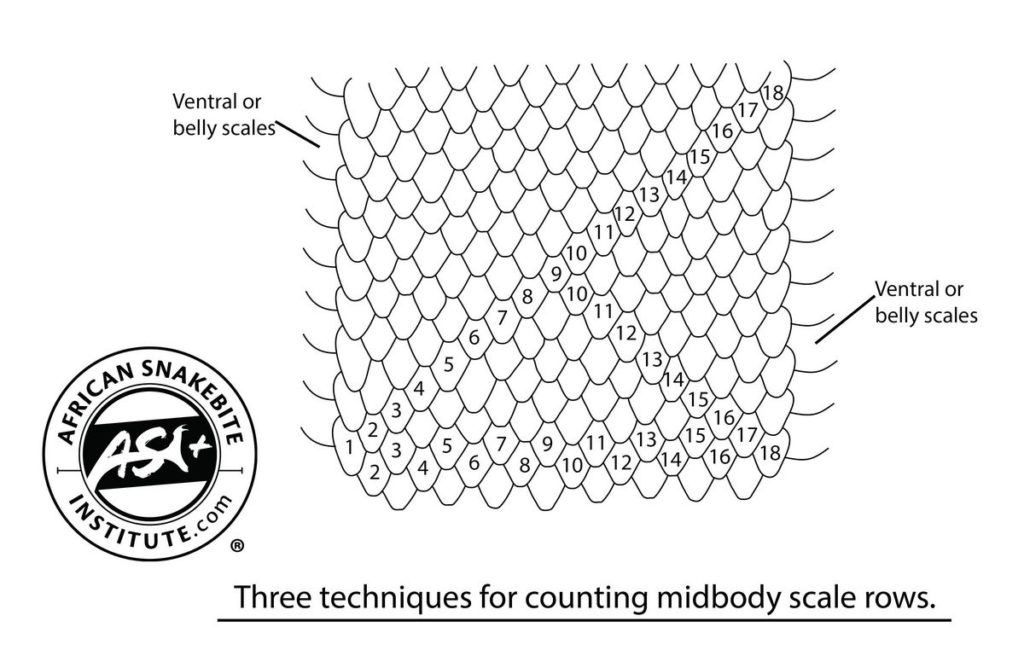

The second important part is the midbody. Counts of scales across the midbody are quite unique, although again, there may be overlap between species. A Brown House Snake will have 25 – 35 scales across midbody whereas a Boulenger’s Garter Snake only has 13.

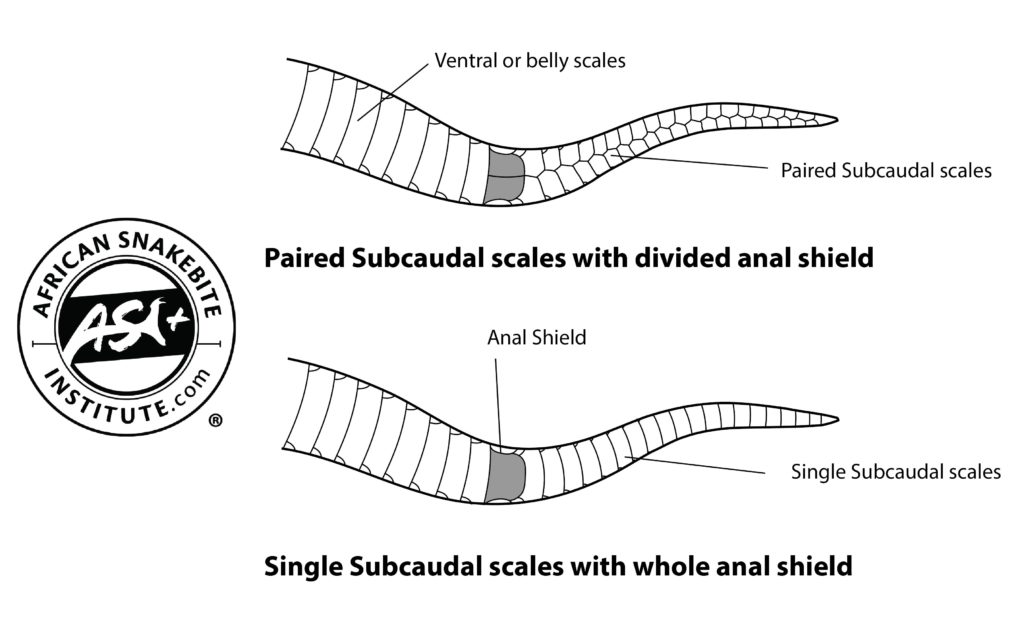

The subcaudal scales and anal shield under the tail are also useful to tell apart some groups such as the small black snakes. Natal Black Snakes have a single row of subcaudal scales, and the anal shield is entire. The Common Purple-glossed Snake’s subcaudals are paired and the anal shield is divided.

Scale counts for all southern African species can be found in the Complete Guide to Snakes of Southern Africa. Other field guides for Africa, such as the Field Guide to East African Reptiles, will have scale counts for the species of those areas. Snake skins are often ripped, and some parts like the head may be missing. In these cases you will have to use what counts you can get and the distribution and you may have to settle for a handful potential of species.

Search

Shopping Cart

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

Featured Products

-

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

-

Rangers Book Combo 2

Rangers Book Combo 2

R2,080.00Original price was: R2,080.00.R1,870.00Current price is: R1,870.00. -

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00