Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

“Muhle wena kona hamba, skati wena bona mamba, noko wena hayi tshetsha, wena ifa lapa stretsha.”

“It’s advisable to hamba, when you stumble on a mamba, for if you do not tshetsha (move), you’ll expire on a stretcher.” – an African saying.

Mambas have a bad reputation in Africa as large aggressive snakes, highly venomous and quick to chase people. The truth is far less exciting. Although the venom of mambas is potent and predominantly neurotoxic, and they are quick in their movements and reactions, they are not aggressive snakes. A wild mamba will flee as soon as possible, often before you even notice the snake. However, because they are fast and nervous snakes, any attempt to capture or corner a mamba or accidentally surprising one may result in a bite. And mambas often bite more than once, in quick succession.

The venom of all four mamba species is largely neurotoxic, causing a collapse of the nervous system and paralysis of the muscles around the lungs, resulting in death if untreated. Occasionally, we see swelling from bites by the Eastern Green Mamba and some bites from Black Mambas have resulted in swelling and discolouration.

It is a common myth that the Black Mamba can kill an adult within a few minutes. While it may well be one of the deadliest snakes in the world, Black Mamba venom, in a case of severe envenomation, will take around 1-7 hours to kill an adult, if the victim is not treated promptly. In exceptional cases, especially with small children, victims may succumb to a bite within half an hour. The venom of all four mamba species is largely neurotoxic, causing a collapse of the nervous system and paralysis of the muscles around the lungs, resulting in death if untreated. Occasionally, we see swelling from bites by the Eastern Green Mamba and some bites from Black Mambas have resulted in swelling and discolouration.

Symptoms may include pins and needles in the lips, a metallic taste in the mouth, difficulty with swallowing, ptosis and dilated pupils, muscular fasciculations, especially in the calf muscles, followed by laboured breathing and eventually a lack of oxygenated blood reaching the brain.

The Genus name Dendroaspis comes from the Latin, dendro, meaning “branch” or “tree” and aspis meaning “snake”, referring to their arboreal lifestyle. Mambas were originally placed in the genus Elaps (being Elapidea – the family of mambas and cobras) by Thomas Triall in 1843 but were later transferred to Dendroaspis by Hermann Schlegel in 1848.

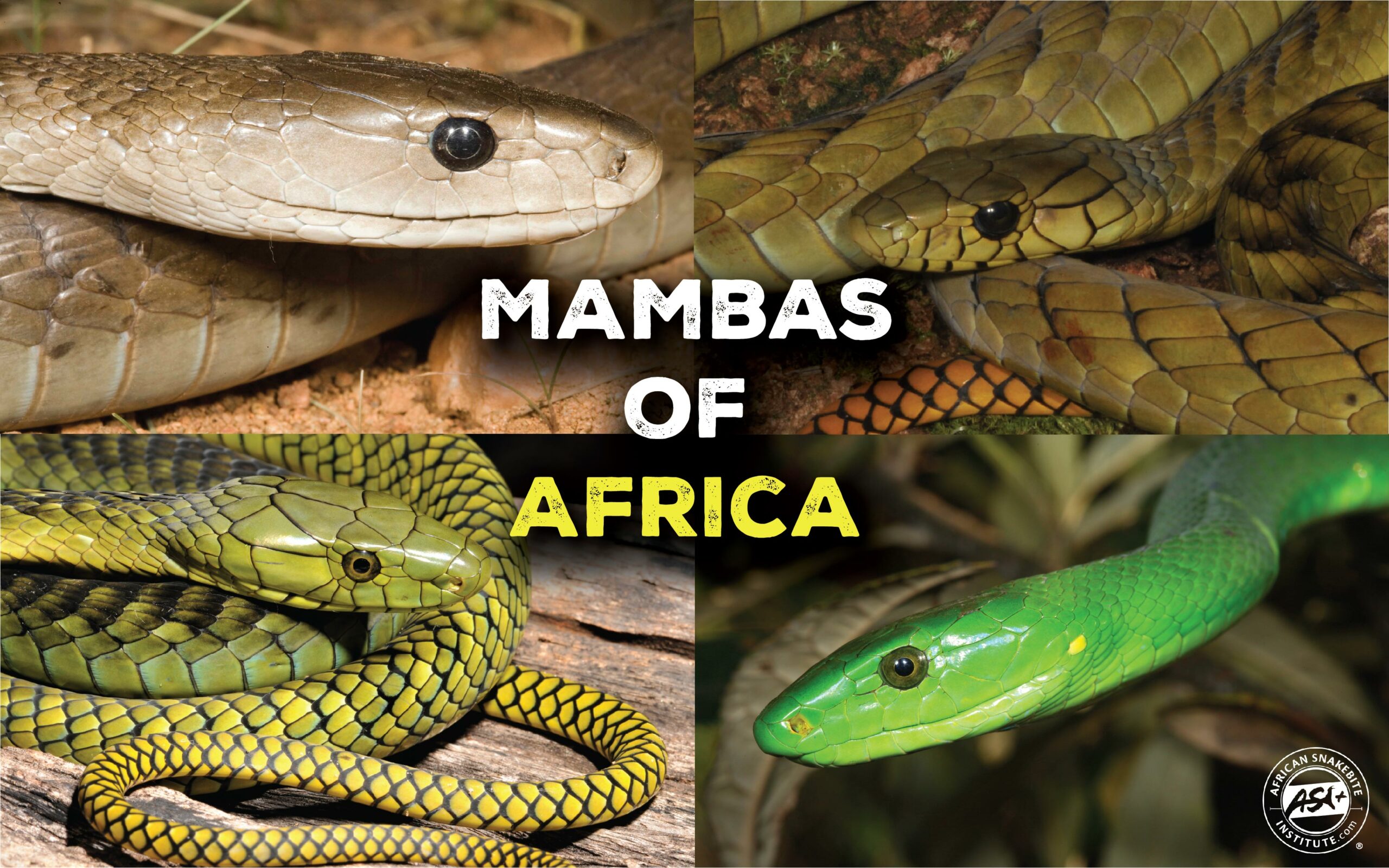

There are four species and one subspecies of mamba, all distributed across sub-Saharan Africa. They are all large snakes, with the Black Mamba attaining the greatest length of the four species.

There are anecdotal records of Black Mambas exceeding four meters in length, however, the late Don Broadley reported the largest Black Mambas in the museum collections (Zimbabwe), which was measured around 2,9 meters. There have been a number of Black Mambas caught by snake removers in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa measuring around 3,2 meters. Older records exceeding four meters may have been from skins in museums. When a snake is skinned, the skin stretches between 20-40%, so a three-meter mamba could easily reach four meters plus if skinned. The three green mambas are smaller than the Black Mamba and reach a maximum length of around 2,5 meters.

Males are often larger than females and all four species are known to engage in male combat in the mating season. Mambas lay eggs and clutches are laid in holes in the ground, in rock crevices or in the hollows of logs and trees. Young Mambas are quite large (30-60 cm) and are highly venomous when they hatch.

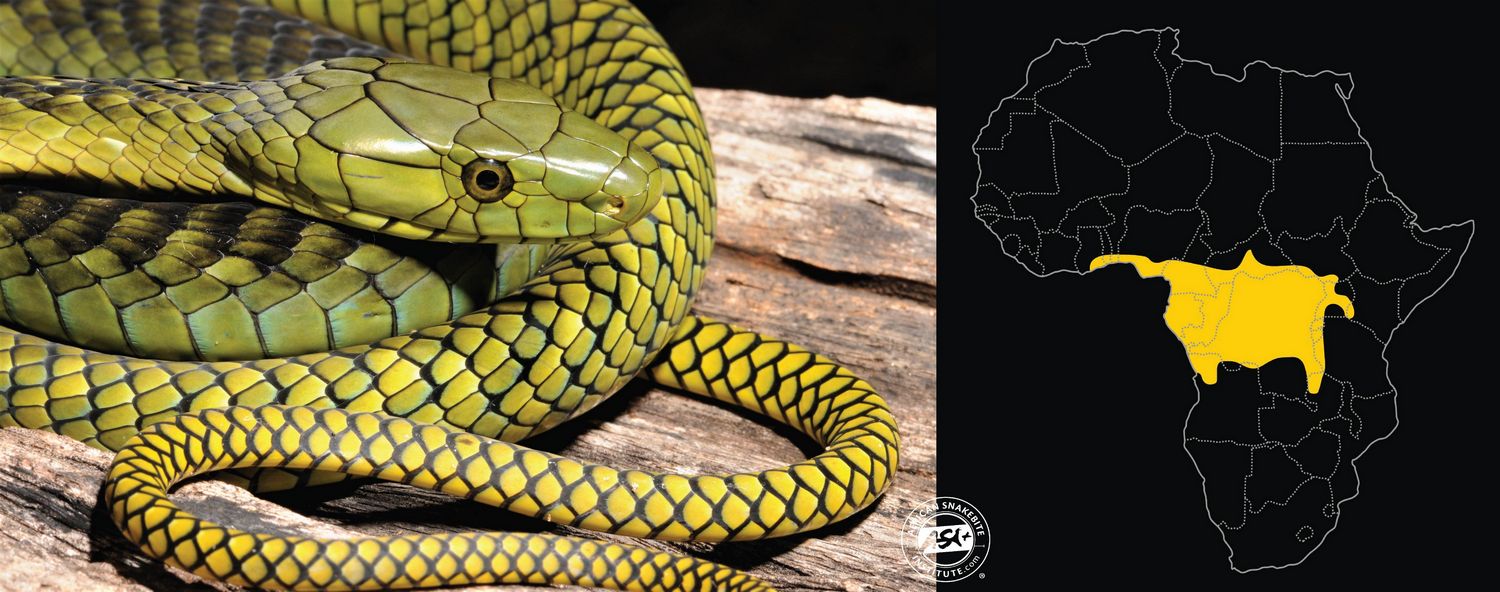

Jameson’s Mamba – Dendroaspis jamesoni (Traill, 1843)

Jameson’s Mamba is a large mamba reaching around 2,6 meters in length. They are olive to lime green, sometimes with some turquoise on the head and often have black markings between the scales or mottled on the body. The Jameson’s Mamba was described by Thomas Stewart Traill, a British zoologist, in 1843. The name jamesonii is in honour of Robert Jameson, a professor of natural history in Scotland. Surprisingly, this is the type species for the genus (first mamba described). The original type locality is listed as South America. This is an error and has been reverted to West Africa. There are two subspecies currently recognised. Dendroaspis jamesoni jamesoni is the nominate species and has a central African distribution from northern Angola to the DRC and Ghana. Dendroaspis jamesoni kaimosae is a subspecies, recognised by having a black tail and lime-green body, and is named after the Kaimosi Forest in western Kenya and described by Arthur Loveridge in 1936. It has a more eastern distribution from eastern DRC through Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and just entering south-western Kenya.

Jameson’s Mamba is at home in tropical jungle, but is equally comfortable in plantations of large trees such as mangoes and nuts. It is a calm species, but when attempting to catch this species it is reportedly very quick and unpredictable. Bites from this snake are not common.

West African Green Mamba – Dendroaspis viridis (Hallowell, 1844)

This was the second Mamba species described. It is large mamba, reaching around 2,4 meters in length. The name viridis comes from the Latin for “green”. It was described by Edward Hallowell, an American herpetologist, in 1844 from a specimen collected from Liberia. It is a yellow-green to light blue snake with black-edged scales. The scales on the head are also black-edged, forming black lines to the eyes. This species occurs throughout the dense forests of West Africa from about Ghana to Senegal. This species is arboreal and can be abundant in thick forest. They are also known to move into plantations and agricultural areas. It is a docile snake, avoiding people and sticking to trees. Bites from this snake are not common.

Eastern Green Mamba – Dendroaspis angusticeps (Smith 1848)

The name angusticeps comes from the Latin angustus meaning “narrow” and ceps referring to the “head” – narrow head. This species was described by Sir Andrew Smith in 1848 collected from Natal. However, by the 1920s, for some strange reason, Green Mambas were considered to just be young or different colour forms of the Black Mamba. The idea at the time was that they were born green and turn black as they age. This probably arises from the fact that Green Mambas are a smaller species than Black Mambas, averaging around 1,5 meters, but reaching 2,2 meters. By 1945, this was corrected, and Green Mambas were accepted as a full species. Green Mambas are a velvety green colour with the occasional random yellow scale. These placid snakes spend most of their lives in trees hunting birds and tree-living mammals. When you come across them, they usually disappear into the dense thick forest vegetation.

Black Mamba – Dendroaspis polylepis (Gunther 1864)

Dendroaspis polylepis comes from the Latin Poly for “many” and lepis, meaning “scales” – many scales. This refers to the high scale count this species has. Surprisingly, this was the last mamba species to be described. It was described by Albert Günther, in 1864, from a skinned animal collected on the Zambezi River in Mozambique. These large agile snakes are usually a grey to olive or brown in colour, sometimes with a darker tail and some barring along the tail section. They are not usually black in colour, although older snakes are often darker in colour and in some regions of Namibia we see darker coloured individuals. The inside of the mouth is inky black and is gaped open when the snake feels threatened. These snakes are well adapted to savannah regions of Africa, being comfortable in trees and on rocky outcrops. In many areas they end up in villages or houses, usually hunting rodents or birds. When confronted, these snakes are reactive and defensive, standing their ground, lifting their head off the ground and often forming a partial hood before striking out and biting. If cornered these snakes are known to bite multiple times in rapid succession. A subspecies, Dendroaspis polylepis antinorii, was described by Wilhelm Peters in 1873 from Ethiopia. It has since been synonymised and is not accepted as a subspecies. It has been suggested that the isolated west African population may be a separate species or at least subspecies, but this required further research.

Mambas are large, graceful snakes that generally avoid humans. Due to their shy nature, sightings of these snakes are special and provided there is some distance between the observer and the snake, are generally safe. However, if the snake feels threatened or cornered, it is advisable to back off. Handling mambas is a dangerous activity that requires a fair amount of experience. It is not advisable for beginner snake handlers to attempt to catch mambas. If you have a mamba in your house or property, use the free ASI SNAKES app and find an experienced local snake remover in the area to safely capture and relocate the snake.

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

Rangers Book Combo 1

Rangers Book Combo 1

ASI Collapsible Snake Hook - 1.2 m

R650.00

ASI Collapsible Snake Hook - 1.2 m

R650.00

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Sign up to have our free monthly newsletter delivered to your inbox:

Before you download this resource, please enter your details:

Before you download this resource, would you like to join our email newsletter list?