Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

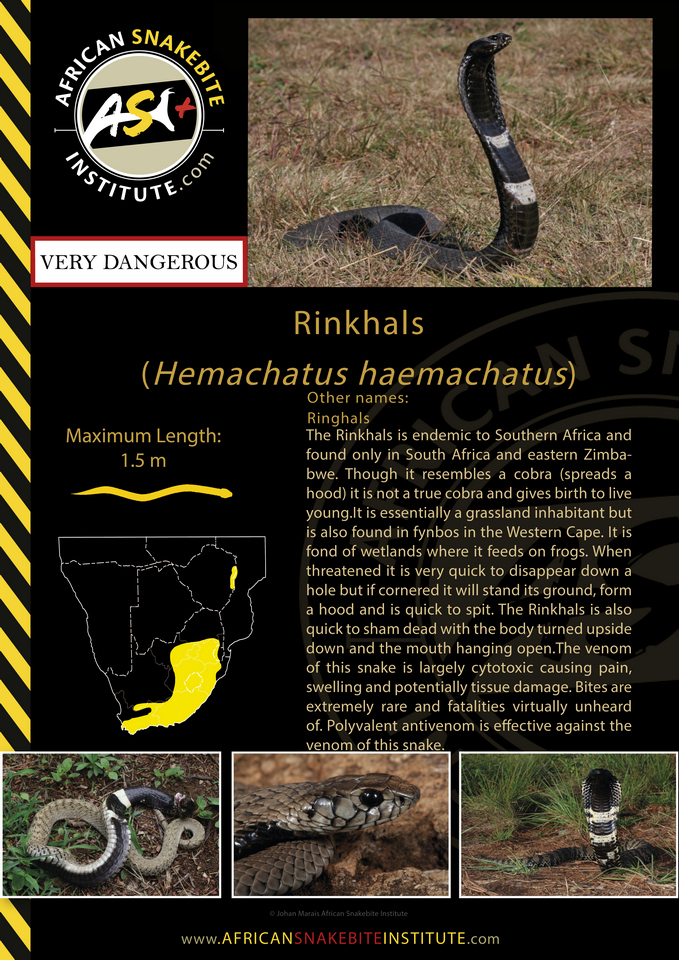

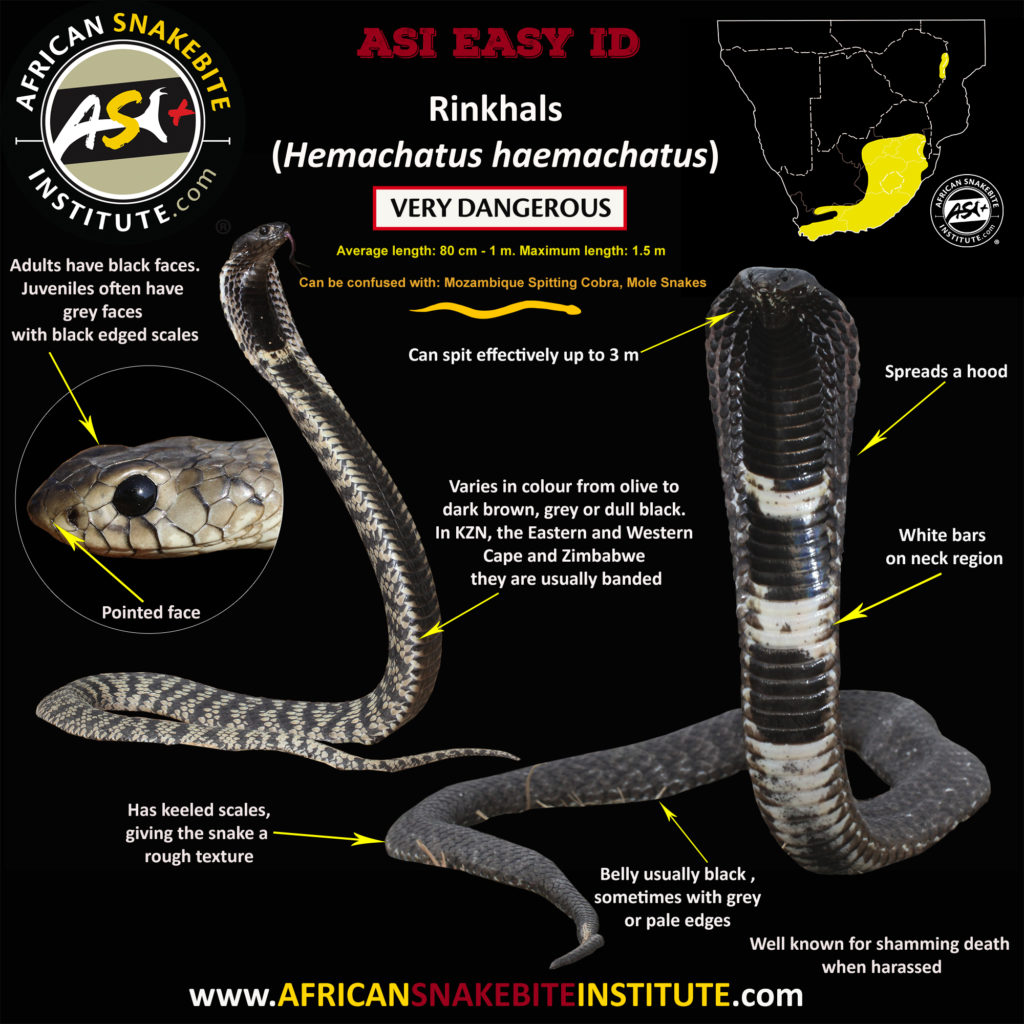

First described by Bonnaterre, back in 1790, the Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus) is a snake often encountered in urban areas of the highveld.

It is closely related to the true cobras of the genus Naja, but actually falls into it’s own genus, Hemachatus – it is the only species in the genus.

Unlike the true cobras, the Rinkhlas has keeled body scales, lacks solid teeth on the maxilla (upper jaw) and produces live young (anything from 20 – 30 babies, but up to as many as 63 per litter).

It’s distribution is restricted to the wetter parts of South Africa, with a relic population in the Nyanga District Zimbabwe.

How stable the population is in Zimbabwe is not known as there have been no recent sightings.

It is a common snake on the Highveld, especially on smallholdings with suitable grasslands and wetlands.

This snake is very partial to toads hence its preference for wetlands but will also feed on rodents, lizards, birds, their eggs and other snakes. Water features or an abundance of toads on a property will lure these snakes.

The Rinkhals is active during the day and is fond of basking, usually close to a hole. As mentioned, it is a shy and retiring snake and is very quick to disappear, but when cornered it will stand its ground, lift up to half of the body off the ground and form a hood – like a cobra.

Their first line of defense is to spit their venom and they generally do so from a reared position, often lunging forward and hissing as they do so. When handled they may spit without rearing up or lunging forward. They do not “throw” their venom, as is often incorrectly stated. They have ample control over their venom glands and spitting action and can accurately aim for human eyes. The spitting action is effective and some venom invariably gets into the eyes, causing immediate pain and severe irritation. This usually gives the snake time to flee. With dogs being natural hunters, they are quick to try and kill a snake, and often get venom in the eyes.

For venom in the eyes, immediately wash the eyes out by keeping them under a gently running tap or hosepipe. Once spat in the eyes the venom immediately does superficial damage to the cornea and inflames the eye lids. By rinsing the eyes with water, any excess venom may be flushed away. Forget about milk, bland liquids or urine – water works best. Then get the person to a doctor (or the dog to a vet) so that the eye can be examined for corneal damage and treated with local anesthetic as well as antibiotic cream (something like Chloramphenicol). This first aid/treatment is highly successful and recovery is usually within 2 – 3 days.

Rinkhals (and a variety of other snakes) are well known for shamming death (this is called thanatosis). When threatened and escape not possible, the snake may turn limp and unresponsive, often with the head and part of the body upside down and the mouth agape. It will appear to be dead, and the strategy is to wait for the predator to clear off, before the snake quickly moves to safety. Should you try and pick the snake up it may strike out quickly.

If all else fails the snake will bite, and although bites on humans are few and far between, a large number of dogs get bitten by this snake. Like other spitting snakes the venom of the Rinkhals is both cytotoxic and neurotoxic, largely causing pain, swelling, blistering and tissue damage. In severe cases of envenomation the victim may also experience difficulty with breathing.

Polyvalent antivenom (manufactured by the South African Vaccine Producers in Johannesburg) is effective against the venom of this snake. Victims should be taken to the nearest hospital (dogs to the nearest vet) quickly and safely for the correct medical treatment. Do not apply any bandages, cut or try and suck out the venom – go straight to hospital. As already mentioned, bites from this snake are quite rare and although considered potentially lethal, there have been no deaths in more than 30 years. Dr. Christiansen reported a fatal bite on a 7 month old child back in a 1981 scientific paper – the only fatality that I am aware of since the 1950’s.

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

ASI Book Combo 1

ASI Book Combo 1

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

ASI Combo C

R1,680.00

ASI Combo C

R1,680.00

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Sign up to have our free monthly newsletter delivered to your inbox:

Before you download this resource, please enter your details:

Before you download this resource, would you like to join our email newsletter list?