PLEASE NOTE. Our offices will be closed from the 12th of December 2025 – until the 5th of January 2026. Last date for orders will be the 8th of December 2025. Any orders placed after the 8th of December 2025, will only be dispatched after the 5th of January 2026.

With around 175 different types of snakes in Southern Africa, the subject of their conservation status is often raised. For many snakes in remote areas of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia, as well as poorly researched areas in South Africa, like parts of the Transkei, Kalahari and the central Karoo, we lack data and know little about some of the snakes that occur there.

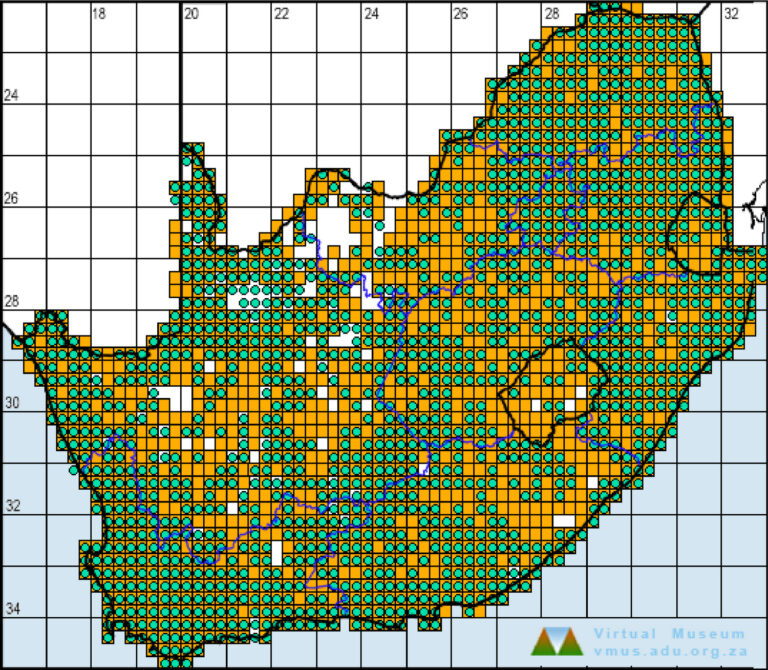

For most of South Africa we have good data and one of the most significant conservation efforts for our snakes was the Reptile Atlas project that started more than 18 years ago. It resulted in the publication of the Reptile Atlas – a comprehensive book in which the conservation status of every reptile in South Africa was listed with additional information, colour photographs and distribution maps. The Reptile Atlas has just been updated and the results of the various conservation assessments of our reptiles will be published soon.

The biggest threat to wildlife is habitat destruction and alteration, this has affected a number of our snakes. Large sections of habitat along coastal KwaZulu-Natal have been destroyed for commercial and residential purposes as well as agriculture, specifically the cultivation of sugarcane and bananas. This is prime habitat for the Green Mamba (Dendroaspis angusticeps) which occurs from the extreme southern tip of coastal KwaZulu-Natal northwards to Kosi Bay and into Mozambique. Over much of its range it is restricted to a narrow coastal strip, often less than three kilometers from the sea, but in northern KwaZulu-Natal it is found up to 45 kilometers inland. It favours dense coastal forest where it spends most of its life in trees and shrubs. The Green Mamba has been proposed to be listed as protected under the Threatened or Protected Species Act (TOPS).

Other threats include the overall impact that people have on snakes. Thousands of snakes are killed by vehicles while crossing roads. During surveys, we will find about a dozen snakes of four or five species on the roads at night, but on a bad night we often find more than a dozen snakes freshly killed by vehicles.

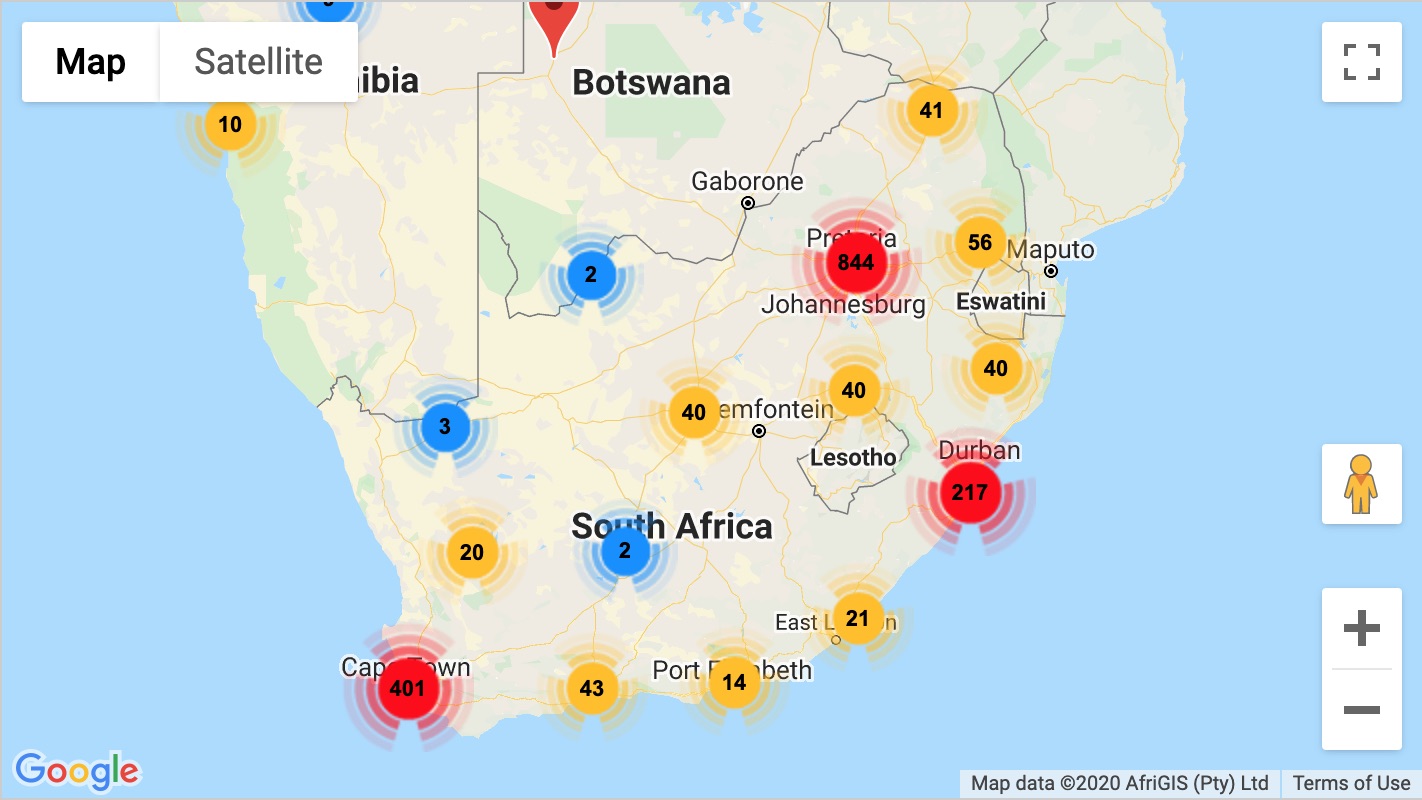

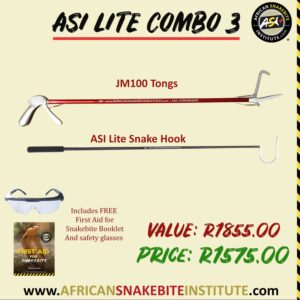

Killing snakes has been common practice for hundreds of years and while growing up in suburban Durban and spending time on various family farms, I witnessed more than my fair share of snakes being killed. Having been in involved in snake conservation and education for more than 45 years, I have seen changes in attitude and more and more people now call a snake remover or purchase snake tongs and attend a snake handling course so that they can relocate snakes and not just kill them. While such killings clearly have a major impact on snakes, it is often common snakes that frequent dwellings in search of food. Some snakes like the Brown House Snake, Slug-eater and Herald Snake have adapted well to urbanization and are common in suburban gardens. Unfortunately, there are a variety of highly venomous snakes that also enter gardens where food is often easily available. More than 200 Black Mambas are removed from gardens and homes in the greater Durban area every year.

The free ASI Snakes app (http://bit.ly/snakebiteapp) has over 250 000 downloads and there are around 800 snake removers listed country-wide that remove problem snakes.

Snake sightings may vary dramatically from year to year, and this is not because of their numbers dropping or increasing annually but rather environmental conditions or abundance of prey that make them more visible. We often hear that a farmer has not seen a single Puff Adder (Bitis arietans) on his farm for four or five years and suddenly he sees four in a few weeks. This has more to do with their behaviour and the fact that they are incredibly well camouflaged. Snakes have many enemies – predatory birds, small carnivores, snake-eating snakes and humans – and are generally secretive and spend much of their lives hidden. We do not have good data on the population size of any snake in Africa and have no idea how many Puff Adders, Green Mambas or Brown House Snakes there are in any country. In fact, we have no idea how many Puff Adders occur on any farm in South Africa and if those numbers had to increase or decrease over a ten-year period, we will be none the wiser.

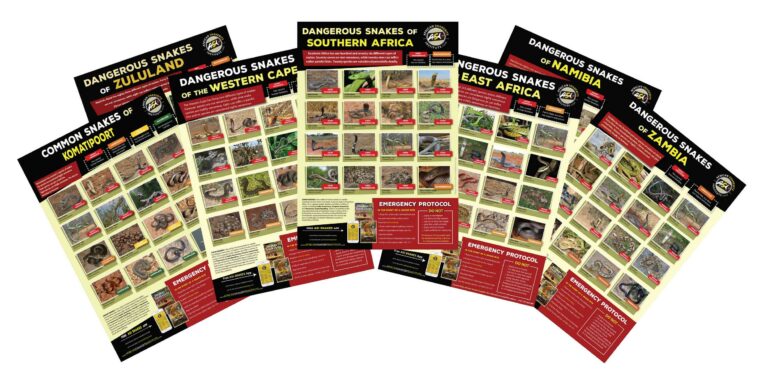

Other than educating the public through books, posters, television programs and social media, there are few initiatives to conserve our snakes. There are many myths and a great deal of misinformation when it comes to snakes, and they generally suffer from a bad press. If a child is bitten by a snake, it is often front-page news, yet compared with vehicle accidents, malaria deaths and various diseases, snakebites are quite rare. The African Snakebite Institute has set the bar when it comes to educating people about snakes and their role in the environment. There are over a million members on our various Facebook pages and our monthly newsletter goes out to around 80 000 people. We have thousands of people attending our snake awareness courses every year and have various resources on our website that can be downloaded for free. This includes posters about snakes of all major cities, various towns, provinces, regions and game and nature reserves in South Africa as well as all southern African countries and many other African countries. If you would like a poster for your area and cannot find one on our website, email snakes@asiorg.coza and we will quickly put one together for you. There are also snake profiles, easy ID profiles, and various newsletters and articles about snakes – go to www.africansnakebiteinstitute.com.

Having snakes removed from properties and released elsewhere is not conservation. It will hardly benefit the species from a conservation point of view, but it will obviously benefit the individual. The conservation benefit is that it sends out the right message – do not kill snakes but rather have a problem snake removed. Ideally, these snakes are removed and released a couple of kilometers away in suitable habitat away from humans and livestock. Releasing a snake 100 km or more away from where it was caught is likely to kill that snake as the climate and habitat may not be suitable and the prey and water sources may not be ideal.

The smuggling of snakes has been problematic for many years and in the past, thousands of snakes were exported to Europe and the USA for the pet trade. These snakes were collected from the wild, held in captivity and shipped out once enough had been accumulated. The majority of these snakes died during transit or soon thereafter. As laws restricting the export of wild snakes were promulgated, exporting them became more and more difficult and the smugglers had to stay ahead of the game. Catching snakes in the wild and keeping or exporting them is now illegal in all provinces except KwaZulu-Natal. Several snake species that are seldom bred in captivity are exported in large numbers out of KwaZulu-Natal and many of these are now provided by unscrupulous ‘snake rescuers’. When gravid snakes are rescued, they are often kept until the female drops the eggs or babies, which are then sold as “captive bred” snakes, an illegal practice that is hard to monitor and control in most provinces. Many come from KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape. This includes Green Mambas and snakes like the Rinkhals. Interprovincial smuggling has also become problematic and hundreds of snakes, like the Rinkhals, are shipped from one province to the other (this is illegal) for extraction of venom but end up being shipped out of the country. The authorities are well aware of these practices and are working on new laws to put a stop to this.

Wildlife trafficking is ranked as the fourth most trafficked item after drugs, arms and human trafficking. Surprisingly it is still a common practice in South Africa and many snake lovers and “conservationists” are involved. Wild snakes belong in the wild and should not be killed, moved or sold. Snake removers and enthusiasts have a responsibility to conserve and protect these animals.

Few of the snakes in southern Africa are of conservation concern. The Albany Adder (Bitis albanica) has a limited distribution near Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth) in the Eastern Cape and the largest colony is on a cement mine, facing habitat alteration. There are various conservation initiatives to conserve this snake and several studies are ongoing. The Namaqua Dwarf Adder (Bitis schneideri) occurs along the west coast from the Olifants River mouth northwards to Lüderitz in Namibia. It inhabits coastal dunes close to the sea where alluvial diamond mining has destroyed much of the suitable habitat. Fortunately, it is widespread and locally abundant. The Gaboon Adder (Bitis gabonica) occurs from Mtunzini northwards into Mozambique and large parts of suitable habitat have been destroyed. It used to be quite common in Dukuduku Forest near St Lucia but that habitat has been cut and cleared by the local community.

There are a number of snakes that are rare and seldom seen and often occur in remote areas. This includes the Plain Mountain Adder (Bitis inornata) that is limited to the Sneeuberg Mountains and surrounding areas near Graaf-Reinet. The Cream-spotted Mountain Snake (Montaspis gilvomaculata) that occurs high up on KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg on the border of Lesotho, described in 1991 and barely seen since. Fisk’s House Snake (Lamprophis fiskii) is found from the Karoo to Namaqualand but is only known from about a dozen live specimens. These snakes are not necessarily of conservation concern but are secretive and poorly studied.

There is a lot of research and awareness still required on snakes in Africa. We know very little about the natural history of many species, such as where they lay eggs, the growth rates and population density. It has been refreshing to see the change in perception in people in southern Africa towards snakes. Having the snake removed or relocating it yourself is slowly becoming more commonplace. People are becoming more fascinated by these amazing animals as the awareness is spreading.

Search

Shopping Cart

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

Featured Products

-

ASI Lite Combo 3

R1,575.00

ASI Lite Combo 3

R1,575.00

-

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00

-

ASI Book Combo 1

ASI Book Combo 1

R1,315.00Original price was: R1,315.00.R1,120.00Current price is: R1,120.00.