Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Snakes have good vision, but it is used mainly for detecting movement. Hence, the old but true saying that if you encounter a snake the best thing to do is to stand perfectly still. Having said that, it would be much better to back off quickly – once you are 5 m or more away from any snake you are safe and cannot be bitten.

Snakes do not strike at stationary objects unless perhaps, they resemble or smell like their prey. Two southern African snakes are believed to have superior vision and are capable of seeing stationary prey – The Boomslang (Dispholidus typus) and the Twig or Vine Snake (Thelotornis species). Furthermore, and for reasons that are not fully understood, these species have binocular vision, much like human vision, while most other snakes have monocular vision. Binocular vision refers to the overlapping visual fields of the two eyes and provides an image that has good depth of field and distance, allowing the snake to accurately perceive its prey in complex surroundings.

Snakes do not have moveable eyelids; instead, a fixed transparent shield that is shed with the rest of the skin during sloughing, covers the eye. This is one feature that can be easily used to differentiate snakes from legless lizards as most lizards have blinking eyelids.

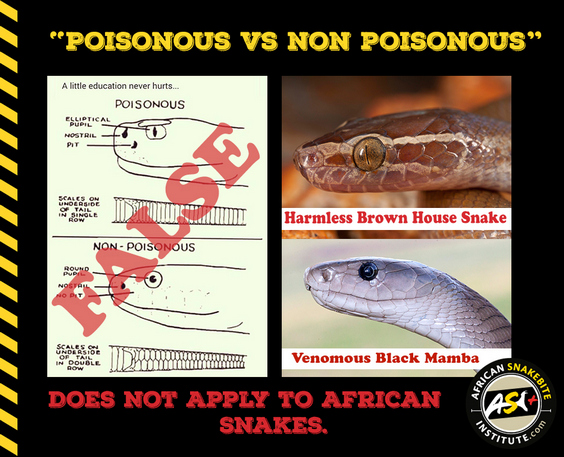

There was a hoax doing the rounds a few years back on the shape of the snake pupil being an indication for whether the snake was venomous or not. This “rule” does not apply to Southern African snakes.

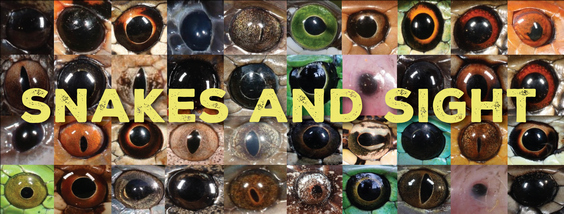

The shape of the pupil, vertically elliptical (cat-like) compared to round, has reference to the snakes’ behaviour. Generally, snakes with vertically elliptical pupils are nocturnal and snakes with round pupils are diurnal. The vertical pupil can still dilate and contract based on the amount of light available.

The position of the eye can also tell a lot about the behaviour of the snake. Many water snakes such as the Dusky-bellied Water Snake (Lycodonomorphus laevissimus) and desert snakes such as Péringuey’s Adder (Bitis peringueyi) have eyes situated on the top of their head. For water snakes, this allows them to ambush from the bottom of a stream or shallows of a dam and also to watch out for predators. For desert-dwelling snakes like Péringuey’s Adder, the snake can bury itself partly into the sand, with only the top of the head sticking out, allowing the snake to ambush passing lizards.

The diameter of the eye compared to the head also explains lifestyles. Arboreal snakes such as the harmless Green Snakes (Philothamnus sp.) and the Boomslang have large eyes with good vision. Terrestrial snakes such as the Sand and Whip Snakes (Psammophis sp.) have medium to large eyes with decent vision. The fossorial species such as Blind Snakes (Afrotyphlops sp.) and Quill-snouted Snakes (Xenocalamus sp.) have small eyes, often with poor vision.

The mechanism in most organisms’ eyes is very similar and is comprised of rods and cones. Snakes are no different. Rods are sensitive to dim light and are responsible for night vision. Cones provide colour vision under bright light. Nocturnal snakes have a higher ratio of rods to cones, allowing them to see better at night. In diurnal snakes, the opposite is true, with more cones than rods.

Some snakes, such as the Pit Vipers and our Southern African Rock Python (Python natalensis) have an additional sense that helps them “see” their surroundings – especially in the pitch-dark nights – called heat sensors. These pits that line the upper lip are thermoreceptors that allow these snakes to sense differences in heat in their surroundings. Since mammals are warm-blooded (endotherms) and generally warmer than their environment (if you think of humans having a body temperature of around 37 degrees Celsius compared to a warm summer’s evening of 25 degrees), the snakes can sense this difference and detect prey such as rodents or, in the case of pythons, small antelope.

It is often said that snakes have poor eyesight, and this is just not true. A warm active Black Mamba will spot a human walking from a fair distance and generally disappear into the nearest tree or rock crevice. Most snakes do not see as well as humans, but pick up movement and react accordingly. Slow and calm movements around snakes, even nervous and alert snakes such as Black Mambas, generally result in a calmer snake than one being threatened by a fast and erratic moving person.

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

Rangers Book Combo 2

Rangers Book Combo 2

Rangers Book Combo 1

Rangers Book Combo 1

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa - 2022 Edition

R550.00

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Sign up to have our free monthly newsletter delivered to your inbox:

Before you download this resource, please enter your details:

Before you download this resource, would you like to join our email newsletter list?