PLEASE NOTE. Our offices will be closed from the 12th of December 2025 – until the 5th of January 2026. Last date for orders will be the 8th of December 2025. Any orders placed after the 8th of December 2025, will only be dispatched after the 5th of January 2026.

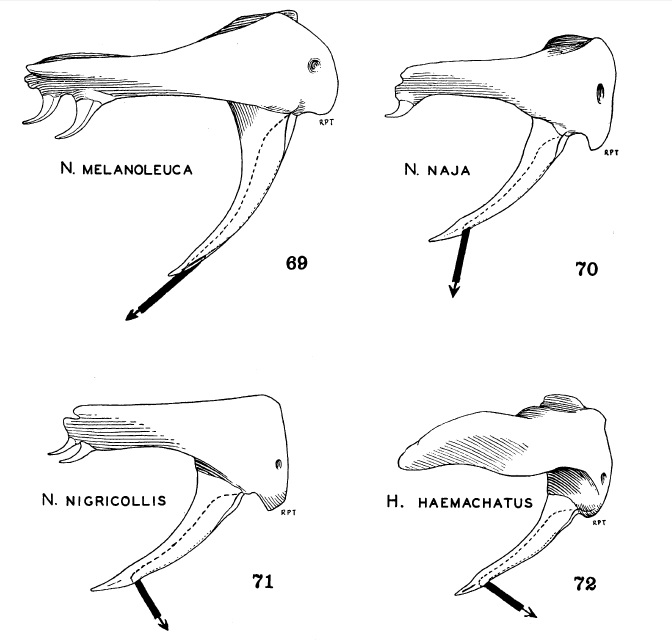

Spitting in snakes is found in some of the cobras of the genus Naja and the Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus). The ability to project or spit venom occurs in both Asian and African Cobras and appears to have evolved separately on both continents. Out of the 33 species of true cobra around the world, spitting has evolved in 15 species, therefore less than half are able to spit venom. In southern Africa, spitting occurs in 4 cobra species and the Rinkhals.

Spitting in snakes is found in some of the cobras of the genus Naja and the Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus). The ability to project or spit venom occurs in both Asian and African Cobras and appears to have evolved separately on both continents. Out of the 33 species of true cobra around the world, spitting has evolved in 15 species, therefore less than half are able to spit venom. In southern Africa, spitting occurs in 4 cobra species and the Rinkhals.

The Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus) is not a true cobra due to a number of morphological features that differ from the true cobras. It has keeled scales compared to the smooth scales of cobras and gives birth to live young whereas cobras lay eggs. The Rinkhals is not as efficient at spitting as the spitting cobras, having a more primitive system. Spitting in the Rinkhals evolved separately to the Asian and African cobras, meaning that spitting has evolved independently three times in the lineage of snakes.

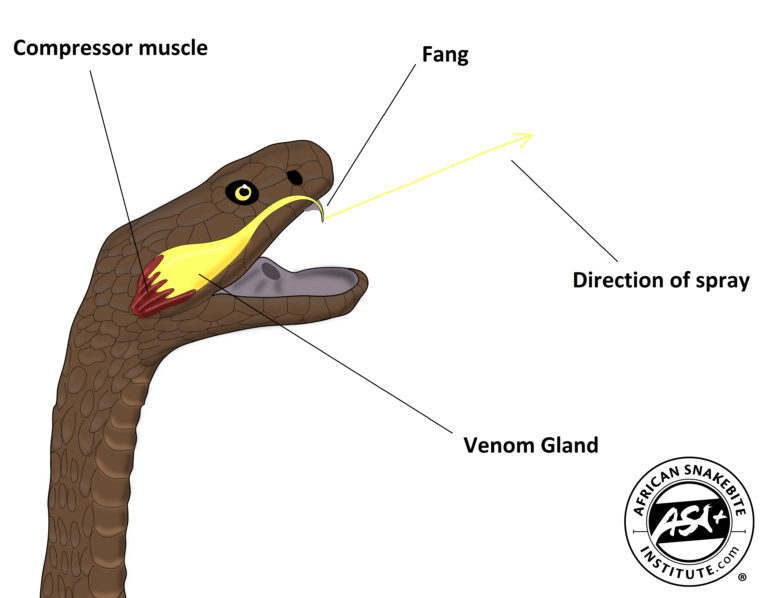

The ability to spit venom occurred due to modifications of physiological features. Firstly, the compressor muscle, used to squeeze the venom glands and inject venom into prey, became enlarged in spitting snakes. The second adaptation was the consistency of venom which became more watery, allowing it to be sprayed better. The structure of the fang itself also changed. The exit opening shifted so that it has a ninety-degree angle to the fang, allowing venom to be sprayed forward instead of downwards. The exit opening was also reduced in size, allowing greater pressure for the venom to be sprayed further, much like placing a thumb over the open end of a hosepipe to create a high-pressure spray.

Unlike Adders and Vipers, elapids (cobras, mambas and their relatives) have short fixed fangs that cannot be moved or fold. Therefore, when a spitting cobra ejects its venom, it must move its head to direct the venom. In video footage of spitting cobras, the snake is often seen moving the head from side to side to successfully hit the target. A recent study on the Red Spitting Cobra (Naja pallida) of Africa showed a hundred percent success rate of the snake venom hitting the target. The study even suggested that the cobra could calculate a moving target and predictively spit ahead to hit the target.

The spitting cobras can still bite people and prey, and venom is easily injected. Spitting the venom is used purely for defence and does not aid in prey capture. Most spitting cobras have around 200 – 300 mg of venom in the two venom glands. The lethal dose (amount required to kill a person) is around 50 mg. When these cobras spit their venom, they usually release around 5 mg of venom per spit, meaning they can spit multiple consecutive times. Most spitting cobras possess a cytotoxic venom that causes damage to the eyes of an attacker.

Thomas Barbour in 1922 wrote a paper on Rattlesnakes and spitting snakes in which he hypothesised that the development of both the rattle in Rattlesnakes and the ability to spit venom in the African cobras was to alert large grazing herbivores of the snakes’ presence and avoid being trodden on. This was a logical hypothesis, as we have seen snakes such as Puff Adders (Bitis arietans) being trodden on by horses, Eland and Giraffe. However, a spitting cobra can only project venom around 8 feet, not nearly far enough to affect the eyes of a giraffe. Barbour said that spitting in snakes outdated man as the ability to spit venom arose around 15 million years ago and so would have developed before humans were around. The African grassland and its mega herbivores only arose and started spreading around 5 million years ago, meaning the ability to spit venom by cobras occurred before the threat of being trodden on was around. Additionally, spitting cobras in Asia developed without grasslands or large herbivores. Wolfgang Wüster suggested that the evolution of spitting cobras arose around the time that apes started evolving in both Africa and Asia. Apes and humans are well known to kill snakes for food or out of fear. The forward-facing eyes of primates makes spitting an effective defence mechanism as both eyes can be temporarily blinded whilst the snake makes an escape. This is only a hypothesis but is well supported with evolutionary timelines of both spitting snakes and primates.

In southern Africa we have 5 species of snakes that can spit venom:

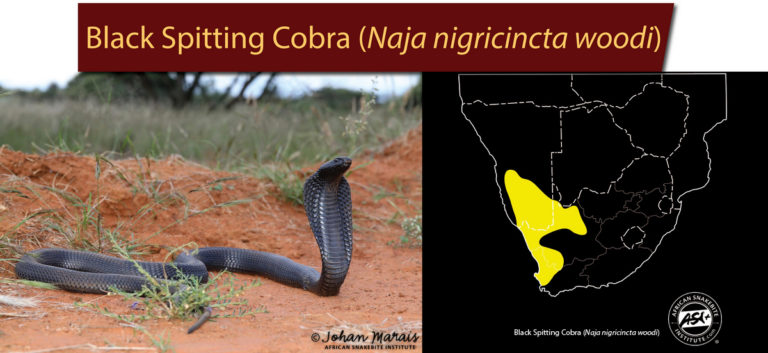

Black Spitting Cobra (Naja nigricincta woodi)

Black Spitting Cobra (Naja nigricincta woodi)

The Black Spitting Cobra is a large cobra of around 1.7 meters in length but can reach up to 2 meters. It is a shy and uncommon cobra, sometimes encountered crossing roads or dry river beds. It is quick to make a hood and spit venom but will avoid humans where possible. It is known from southern Namibia, the Namaqualand region of southern Africa and south to the southern Cederberg. It is a shiny pitch-black cobra that is sometimes confused with a dark Cape Cobra (Naja nivea) or large Mole Snakes (Pseudaspis cana). Bites are rare due to the skittish nature of this species.

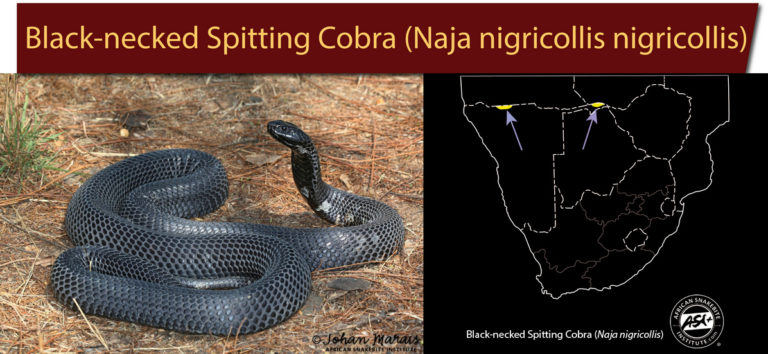

Black-necked Spitting Cobra (Naja nigricollis nigricollis)

The Black-necked Spitting Cobra is a large cobra that can exceed 2 meters in length. It is common further north in Africa, but only occurs in northern Namibia and the Caprivi strip as well as extreme northern Mozambique in southern Africa and is not encountered frequently. Further north in its range, the Black-necked Spitting Cobra may be common around human dwellings and fowl runs. It is quick to spread a narrow hood and spits venom with ease around 2m or more depending on the size of the snake. This large cobra is similar in appearance to the Mozambique Spitting Cobra and is uniform dark olive brown to grey-brown or black above, with a yellow to red belly.

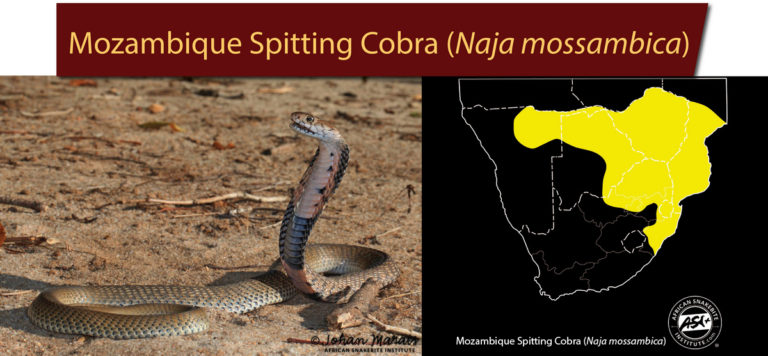

Mozambique Spitting Cobra (Naja mossambica)

Mozambique Spitting Cobra (Naja mossambica)

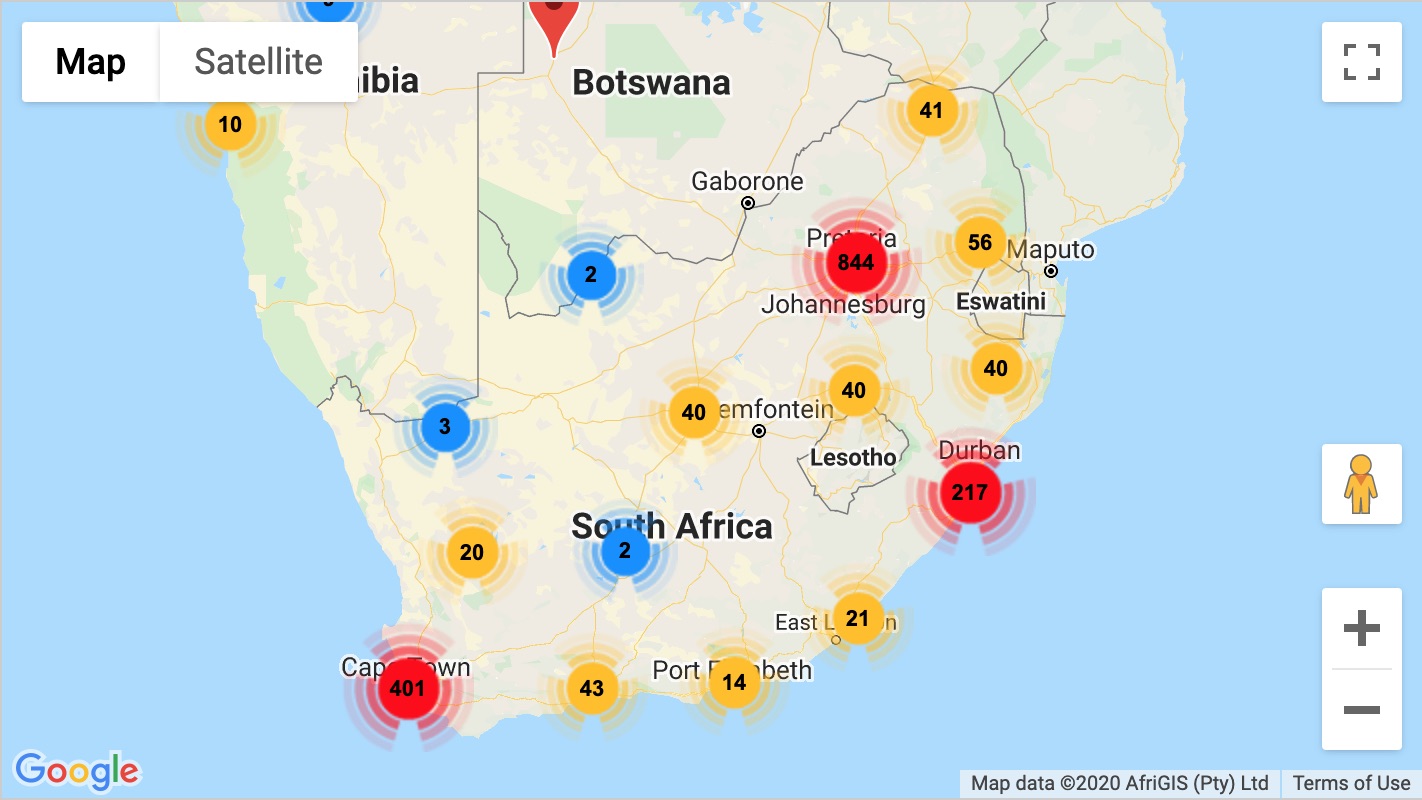

The Mozambique Spitting Cobra is a medium to large cobra that can exceed 1.7 meters in length. It is a common species in most of its range, often found around human dwellings. It is known to enter houses at night and bite sleeping victims, often on the hands and face. It is also quick to spit its venom and can do so without forming a hood and may even spit from a concealed rock crack or crevice. The Mozambique Spitting Cobra accounts for the most bites in southern Africa, followed by the Puff Adder (Bitis arietans). The cytotoxic venom causes tissue damage, but fatalities are rare.

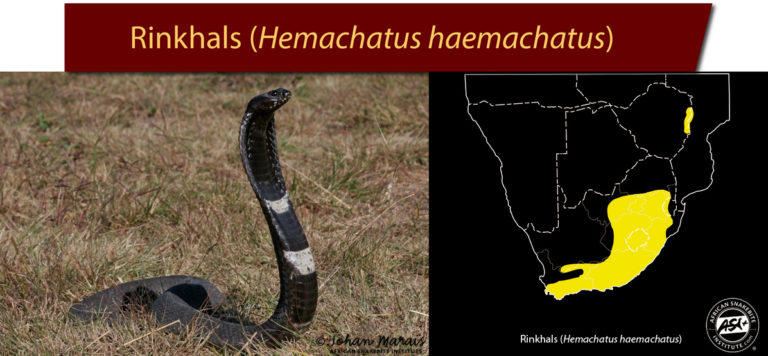

Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus)

Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus)

A medium sized snake of around 1.5 meters. The Rinkhals is a common species in grasslands, especially around Johannesburg and the grasslands of Mpumalanga. In the Cape it is less common and has not been seen around the Cape flats for many years. There is a relic population in the Zimbabwe eastern highlands that also appears scarce. The Rinkhals is quick to hood and spit its venom but will disappear down the nearest hole or into thick grass if given the chance. It almost always spits its venom from a hooded position, lunging forward as it spits the venom. If it is harassed or threatened it may also play dead, rolling over and opening the mouth. If handled at this stage it may bite and is best left alone. As soon as the threat has past the Rinkhals will correct itself and make a quick escape. Bites to humans are rare, but venom in eyes to both humans and pets, such as dogs, is common.  Zebra Cobra (Naja nigricincta nigricincta)

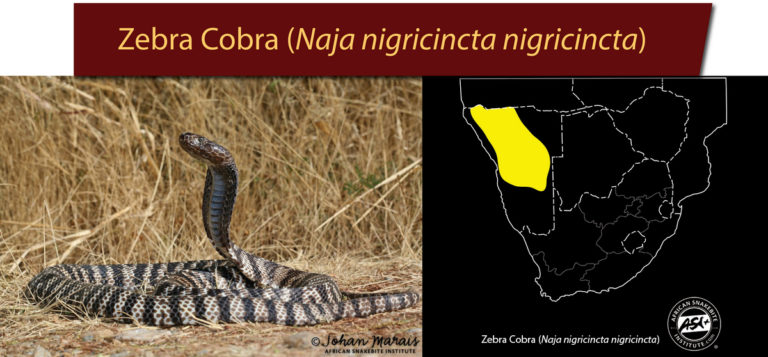

Zebra Cobra (Naja nigricincta nigricincta)

A medium sized cobra that reaches around 1.5 meters in length. It is common in most of its range, often occurring around human dwellings. The Zebra Cobra or Western Barred Spitting Cobra as it is sometimes called, spits its venom with ease and accounts for many bites in Namibia. It is also known to enter houses at night and bites victims in their sleep. Antivenom is not particularly effective against this species and most bites are treated for necrosis and wound management.

Venom in the eyes is not uncommon for people in areas where spitting cobras occur. Snake catchers are often spat at when handling these snakes. A pair of sunglasses is sufficient to prevent venom in the eyes although safety glasses that seal around the eyes are recommended. Venom in the hair or on the skin poses no threat and can be washed off with water. Venom in the mouth, aside for a bitter taste, usually poses no threat as it is a protein and will be digested. Even open wounds pose little threat as the amount of venom spat is so little. When venom gets into the eyes, it causes instant pain and inflammation as it attacks the tissue. The eyes of both people and pets must be washed with water for a period of around 20 minutes, flushing out excess venom. Any neutral liquid will suffice, and milk or urine is not required or suggested unless water is not available. Antibacterial cream should be applied and will prevent any secondary infections. If venom is left in the eyes, it can cause permanent blindness and many people in rural Africa have suffered from spitting cobras. In the event of someone being spat in the eyes, it is recommended that after rinsing the eyes for 20 minutes with water, a doctor should be consulted to check for corneal damage.

Venom in the eyes is not uncommon for people in areas where spitting cobras occur. Snake catchers are often spat at when handling these snakes. A pair of sunglasses is sufficient to prevent venom in the eyes although safety glasses that seal around the eyes are recommended. Venom in the hair or on the skin poses no threat and can be washed off with water. Venom in the mouth, aside for a bitter taste, usually poses no threat as it is a protein and will be digested. Even open wounds pose little threat as the amount of venom spat is so little. When venom gets into the eyes, it causes instant pain and inflammation as it attacks the tissue. The eyes of both people and pets must be washed with water for a period of around 20 minutes, flushing out excess venom. Any neutral liquid will suffice, and milk or urine is not required or suggested unless water is not available. Antibacterial cream should be applied and will prevent any secondary infections. If venom is left in the eyes, it can cause permanent blindness and many people in rural Africa have suffered from spitting cobras. In the event of someone being spat in the eyes, it is recommended that after rinsing the eyes for 20 minutes with water, a doctor should be consulted to check for corneal damage.

Many snake catchers or handlers often build up a sensitivity to spitting snakes and have an allergic reaction often sneezing uncontrollably, but in sever cases, causing difficulty in breathing, tearing of the eyes and rashes on the body. For handlers and collectors who deal with spitting snakes it is advisable to use a face mask when handling the snakes or cleaning tanks to prevent the sensitivity and reaction. In cases where a person experiences these symptoms, it is advisable to discuss obtaining a EpiPen (standardized dose of adrenalin) with a medical doctor. This could be life-saving in cases of anaphylaxis.

Search

Shopping Cart

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

Featured Products

-

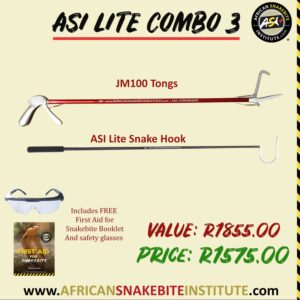

ASI Lite Combo 3

R1,575.00

ASI Lite Combo 3

R1,575.00

-

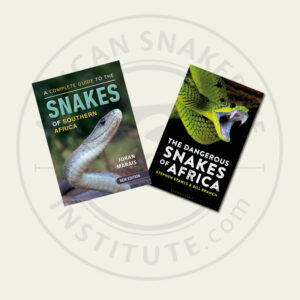

ASI Book Combo 1

ASI Book Combo 1

R1,315.00Original price was: R1,315.00.R1,120.00Current price is: R1,120.00. -

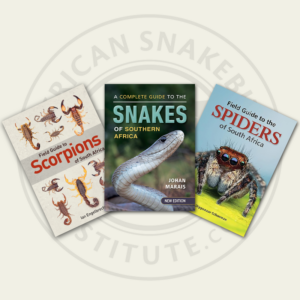

Rangers Book Combo 1

Rangers Book Combo 1

R1,450.00Original price was: R1,450.00.R1,305.00Current price is: R1,305.00.