Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

What is a virtual Museum?

Museums hold a selection of animals, usually multiple specimens from different regions across the range. Each specimen has a label that gives identification, collection date and most importantly, coordinates for the location of where the specimen was collected from. Scientists and academics use these specimens, and attached information, to describe species and create the distribution maps we use in field guides.

There are four major museums in South Africa that collect reptiles with a curator who looks after the collection and adds specimens. There are probably around 100 people in the whole of South Africa who add reptile specimens to Museums. These 100 people, mainly students, museum staff and enthusiastic naturalists, have added around 85 000 specimens to the Ditsong Museum and around 38 000 specimens in the Port Elizabeth Museum since collections started in South Africa.

There are around 50 million people in South Africa, if less than one percent is interested in nature and of that one percent, five percent have a basic interest in reptiles, we have 25 000 people around the country who see and potentially photograph reptiles. These numbers are just a guess as we have over 120 000 members on the Snakes of South Africa Facebook page who add records daily. If 100 people can add over 123 000 records between two museums, imagine what 25 000 people could do?

The idea of a Virtual Museum is for records of animals to be submitted to a database system and cataloged with identification and location coordinates. This allows us to create distribution maps with additional data. Essentially, it is a museum collection made up of photographs instead of dead animals. These records, with their coordinates, are essential for up-to-date distribution maps and our knowledge of species ranges. With data being collected over the years, we can also compare how prevalent a species is each year compared to environmental conditions like rainfall. Many areas are under-sampled and there are large areas (like the Northern Cape) where we don’t know what species occur there. If one farmer in the area snapped pics on his cell phone and uploaded them to one of the virtual museums, we’d have a better understanding of distribution ranges and probably have a lot of range extensions.

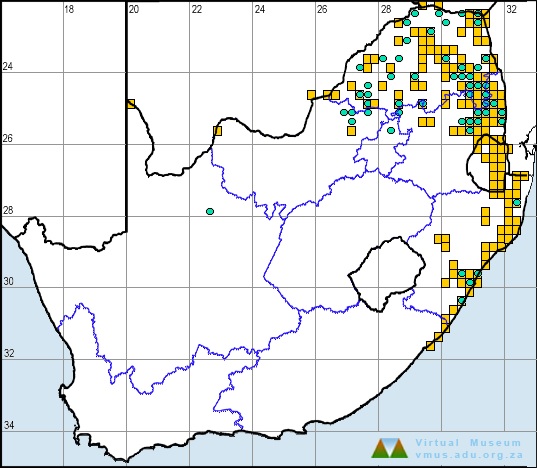

An example – we have a lot of people on social media telling us about all the Black Mambas they’ve seen in the Northern Cape (around Kuruman and Prieska), yet we have only one Black Mamba record in the Northern Cape collected by the McGregor Musuem in Kimberley. If these people would upload a single photograph and coordinates, we could update the distribution maps to include the Northern Cape.

Distribution map on ADU for Black Mamba – blue dots are citizen scientist records – note the single Northern Cape record. If more records were uploaded, we could fill the map and extend the known distribution.

Where can you upload records?

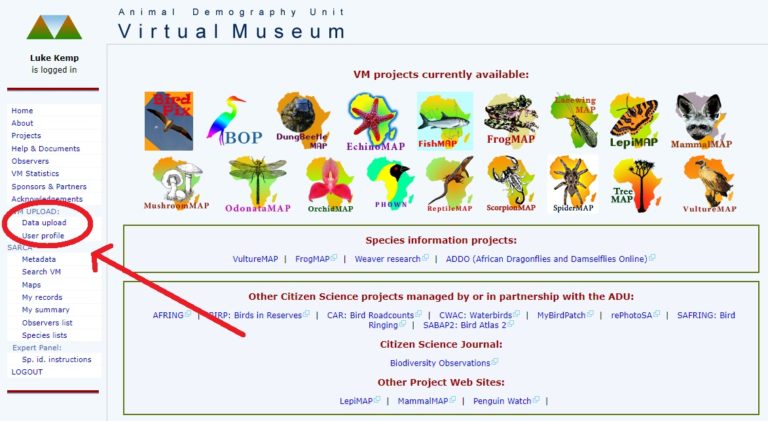

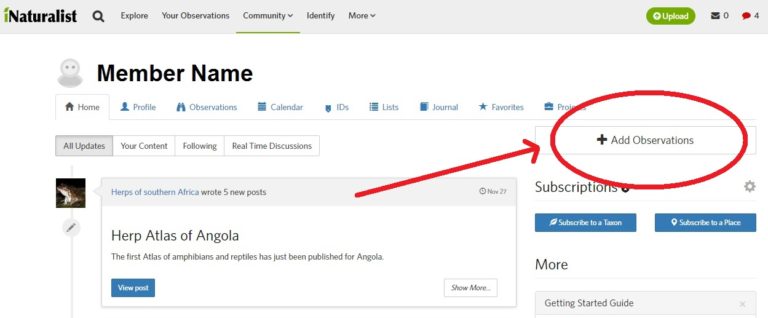

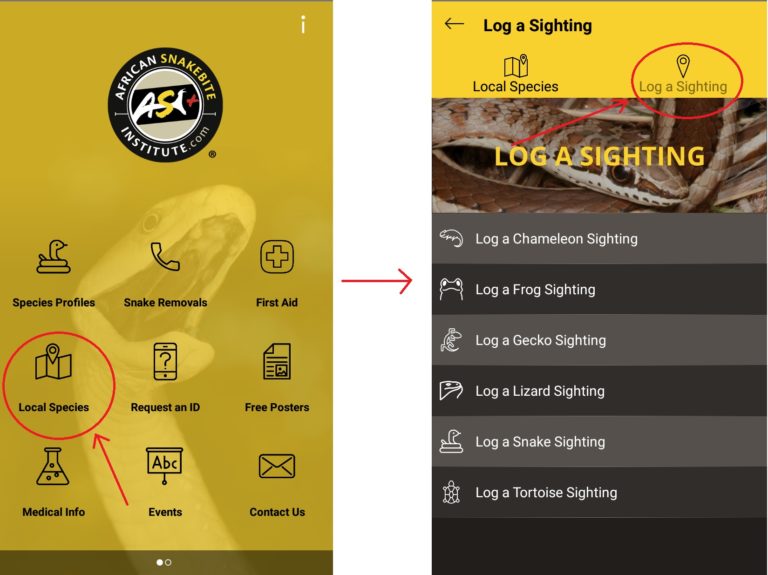

There are two major Virtual Museum platforms: The Animal Demography Unit (ADU) and INaturalist (used to be Ispot). The data from both projects are managed by the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) and are used for the Atlas and Red list of Reptiles – a conservation assessment used to protect threatened species. The African Snakebite Institute app has a feature where you can log a sighting, these records get added to the ADU. Internationally, there is a project called HerpMapper that also takes records of reptiles.

How does it work ?

Adding records is very simple. After signing up, one to three photos of the sighting can be used per record (helps to have different angles for hard-to-identify species). These photos and a coordinate (GPS coordinates or a dropped pin on the project maps) are submitted to the project. These records are then identified by members of the project and added to the database and maps. On the ADU maps, Blue dots are “citizen scientist” records and yellow are museum records (often very old and sometimes questionable).

Home page for the Animal Demography Unit (ADU) – arrow shows where to upload records. ADU has a variety of maps with an expert panel to identify your records.

Home page for INaturalist with record submission circled. Any flora and fauna can be submitted, and you can help identify records as part of a community based identification panel.

On the ASI app, you can log a sighting – this feature allows you to log your records with all your details. This sighting will then be uploaded to ADU over time.

Why should you help?

Virtual museums help our understanding of reptile distributions and expand the distribution databases for each species. The records confirm the presence of a species at a particular point in time and provide range extensions or fill gaps in areas that are under-sampled. This helps with conservation assessments as we get a better understanding of the extension of the range of species.

For example, the critically Endangered Salt Marsh Gecko (Cryptactites peringueyi) was only known from two locations in the Eastern Cape. Around St Francis there was concern that new housing development may destroy habitat and threaten the species. Recently, students have found them at another two locations, doubling the known locations and moving the species assessment from Critically Endangered to Near Threatened. With so many people taking pics with their phones these days, it would be easy to double or triple the amount of records we currently have of most species if the pics were just uploaded with a location.

Currently on the Animal Demography Unit there are just over 28 000 records (including some museum records) since 1994. The birders use a platform called BirdLasser (SABAP). They upload over a million records a year in Southern Africa. Due to this, bird distributions are well known. If reptiles received a tenth of the amount of interest as the birders have, we should be adding triple our current records a year! Snake removers could easily snap a pic and keep record of what they’ve removed and from where by adding them to a database system. The Snakes of South Africa Facebook page must receive 30 – 50 records a day that never get logged. That’s around 15 000 records a year that are wasted. Let’s get more people interested in uploading records to virtual museums and becoming Citizen Scientists.

Snap it and map it!

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

ASI Book Combo 2

ASI Book Combo 2

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00

ASI First Aid for Snakebite Booklet

R40.00

ASI Book Combo 1

ASI Book Combo 1

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Sign up to have our free monthly newsletter delivered to your inbox:

Before you download this resource, please enter your details:

Before you download this resource, would you like to join our email newsletter list?