Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

A recent social media post claimed that, following a snakebite, chewing the bark of a cashew nut tree would neutralize the venom of the snake and ensure the full recovery of the victim. In many tropical African countries, cashew nut trees are common and often line the streets around villages. It would be an ideal first aid for snakebite, if true. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that it works and furthermore, raw cashew nuts and the bark contain urushiol, a toxin known to cause allergic reactions in humans.

The World Health Organization estimates that deaths by snakebite in sub-Saharan Africa range between 20 000 – 32 000 each year. This is based on available data and is quite likely an underestimation. Not all snakebite victims are treated in hospitals, especially so in poorer countries and rural areas. Many are treated with traditional remedies and die before ever reaching a hospital. These deaths are not always documented or reported.

Snakebite in Mozambique are estimated to cause around 300 deaths per year. A recent publication conducted just over a thousand household surveys in the Cabo Delgado province in northern Mozambique and estimated that there are over 6000 bites per year, and around 800 deaths, just in that province. They extrapolated this data and conservatively suggested that there are around 69 000 bites and almost 9 000 deaths a year – just in Mozambique!

Most of the population in Mozambique (around 68%) live in rural areas and rely on subsistence farming. These people are often exposed to snakes, and many are bitten. Unfortunately, around 60% of bites are treated by traditional remedies. Only 15% seek medical attention at hospitals. Around 25% die before reaching hospitals.

In the Benue Valley of northern Nigeria, snakebite is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among farmers and hunters (Warrell, 2008). Morbidity from snakebite often leads to the loss of limbs and will negatively affect a farmer’s ability to provide for his family.

Treating snakebite in a hospital, even without the use of antivenom, is quite manageable and for most bites (cytotoxic – such as Puff Adders and Mozambique Spitting Cobras), requires careful monitoring of fluids, managing swelling and tissue damage as well as organ failure. For neurotoxic bites (like Black Mambas) it requires careful management of breathing. A paper from Ngwelezane Hospital in rural KwaZulu-Natal had 879 snake bites over five years and not a single fatality. Another paper from rural KZN had 164 patients with no deaths (Coetzer & Tilbury, 1982) and Sloan et al. (2007) interviewed 50 snakebite patients in hospitals and none died. Snakebite in hospital is treatable and mostly with a good outcome.

Currently there are no known traditional remedies that work against the venom of highly venomous snakes or relieve the symptoms of serious snakebite envenomation. One of the problems with traditional remedies, whether they are cultural or from farmers, is that they are anecdotal: a single case upon which the whole theory is based. For example, a person gets bitten by a harmless Brown House Snake, but misidentifies it or believes the snake is a dangerous cobra. The person then tries a traditional remedy – a muthi, chewing cashew nut bark, drinking milk, cutting and sucking at the bite site – and survives the ordeal. They now believe that the remedy they used will cure a bite from a venomous snake.

If a person is bitten by a highly venomous snake such as a Black Mamba and is envenomated, they are going to struggle to breathe over the next few hours that follow, and they need to get to a hospital where they can be placed on a ventilator. Seeking out traditional remedies that most likely will not work is time wasted and could cost valuable time needed in a hospital.

In 1986, an American missionary physician, who practiced in the Amazon in Ecuador, reported that he had successfully treated 34 snakebites with electric shock and not a single patient had died. This practice spread swiftly around the world and was widely used in the United States. It was quickly disregarded however, as snakebite patients from serious Rattlesnake bites deteriorated rapidly without the correct treatment of antivenom. It was later determined that the physician had been treating bites from lesser venomous pit vipers and that the patients would not have died even without the use of shock therapy (Dart and Gustafson, 1991). Subsequent experiments have shown that electric current does not neutralize snake venom.

A study by Sloan et al. (2007) showed that in Hlabisa sub-district in KwaZulu Natal, 80% of patients used traditional remedies and 62.5% consulted traditional healers, resulting in delays of up to six hours before getting to a hospital. In bites from Black Mambas, victims are usually critical between 2-7 hours following the bite, so visiting a traditional healer is likely to result in the victim succumbing to respiratory failure before reaching a hospital. In cytotoxic bites, the longer a victim takes to get to a hospital, the more tissue damage results. Tissue damage is not reversable and often requires skin grafts, surgery and even amputation. This means extended hospital stays, which, in a rural and lower- to middle-class context, implies a loss of income while the victim is unable to work.

In South Africa, a local snakebite medicine, known as isibiba is used in around 80% of all bites. It is freely available from most traditional healers, and even online, at around R 25.00 per treatment. In most snakebite deaths that we see each year in KwaZulu-Natal, the patient had taken isibiba and almost always had xaba (scarification) treatment performed. This unfortunately shows that it is not effective in treating highly venomous bites. Additionally, xaba (scarification) treatment is usually performed in the event of cytotoxic bites (because snakes with cytotoxic venom are responsible for 80% of serious snakebites in South Africa), and infections resulting from the cuts are common and often resulted in serious tissue damage that requires surgical intervention.

A major challenge in Africa is access to medical facilities. In the study by Sloan et al. (2007), they showed that on average, it took victims just over 7 hours to reach a medical facility, whereas the average time to reach a traditional healer was only 15 minutes.

Data captured from bites in South Africa show that the majority of bites (80-96%) occur on the foot or lower limb (12% to hands) in rural areas and occur between 18:00-20:00 during the summer months (November to March) where people are walking barefoot. In most bites, only a single fang puncture was present, probably resulting in reduced envenomation. Between 10-12% of victims required antivenom – the rest could be treated symptomatically (Coetzer & Tilbury, 1982). To reduce snakebites, issuing gumboots and torches to rural communities may be an effective solution.

As we move into summer and the rainy season, we will see an increase in snake encounters and unfortunately, snakebites. For serious bites from venomous and highly venomous snakes, the best and only first aid is to get to a hospital; preferably one with a trauma unit. Hospitals can quite easily treat snakebite with very high success rates. Traditional remedies are not proven to help with snakebites and could cause more damage than good, while delaying correct treatment from the hospital.

CONTACT US:

Product enquiries:

Caylen White

+27 60 957 2713

info@asiorg.co.za

Public Courses and Corporate training:

Michelle Pretorius

+27 64 704 7229

courses@asiorg.co.za

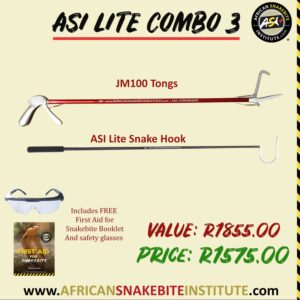

ASI Lite Combo 3

R1,575.00

ASI Lite Combo 3

R1,575.00

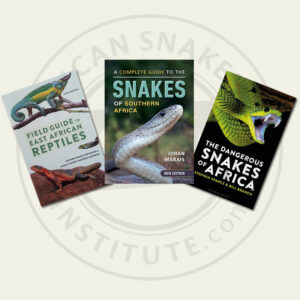

ASI Book Combo 2

ASI Book Combo 2

ASI Combo C

R1,680.00

ASI Combo C

R1,680.00

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Want to attend the course but can’t make it on this date?

Fill in your details below and we’ll notify you when we next present a course in this area:

Sign up to have our free monthly newsletter delivered to your inbox:

Before you download this resource, please enter your details:

Before you download this resource, would you like to join our email newsletter list?